Leadership and Ethics

Shermin Kruse

Graduate students go on to become future leaders in the worlds of business, law firms, politics, non-profit, and public policy. Therefore, it is important that this global transactions textbook also consider appropriate and ethical leadership.

While all of those reading this book likely have ambition, determination, and a strong work ethic, there are other essential qualities to outstanding leadership. Whether the issue playing itself out in society is a global pandemic that adversely affects certain segments of society, continued systemic racism and police brutality against minority communities, or the innovation and technological advancement that are impacted by a corporation’s ethics, corporate leaders should always envision ourselves as those with the power and influence necessary to lead those movements, discussions, and actions.

Typical Leadership Models

Traditionally, there are six leadership models taught by MBA programs, law schools, and leadership training programs: Coercive, Authoritative, Affiliative, Democratic, Coaching, and Pacesetting.

We will examine each of these, then propose a new leadership model that combines the best aspects of each of the traditional models: Transformative Leadership.

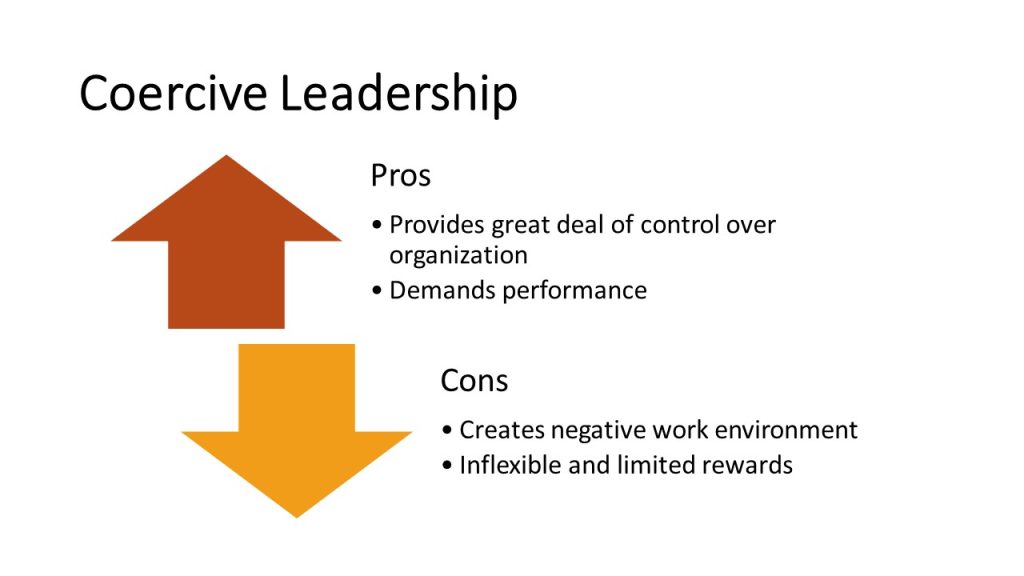

1. Coercive Model of Leadership

In this model of leadership, power is derived from the authority to punish. It is, in many respects, the most obvious type of power. Words that might be used to describe this kind of individual include: relentless, overbearing, unyielding, persistent, harsh, and ruthless. Examples of coercive power include: threats of write-ups, demotions, pay cuts, layoffs, terminations, and then follow through. Consider for a moment who might be a coercive leader now. Any particular US president (Donald Trump?), past or current employer, or even friend or parent? Give thought to their leadership style. While problematic at times, consider where there can be any benefits to this style of leading.

While coercive leadership might be appropriate in certain circumstances, given its negative impact on the work environment and the extent to which it can stifle innovation, it should be a last resort for great leaders, appropriate only (if ever) in times of crisis, and even then only short term.

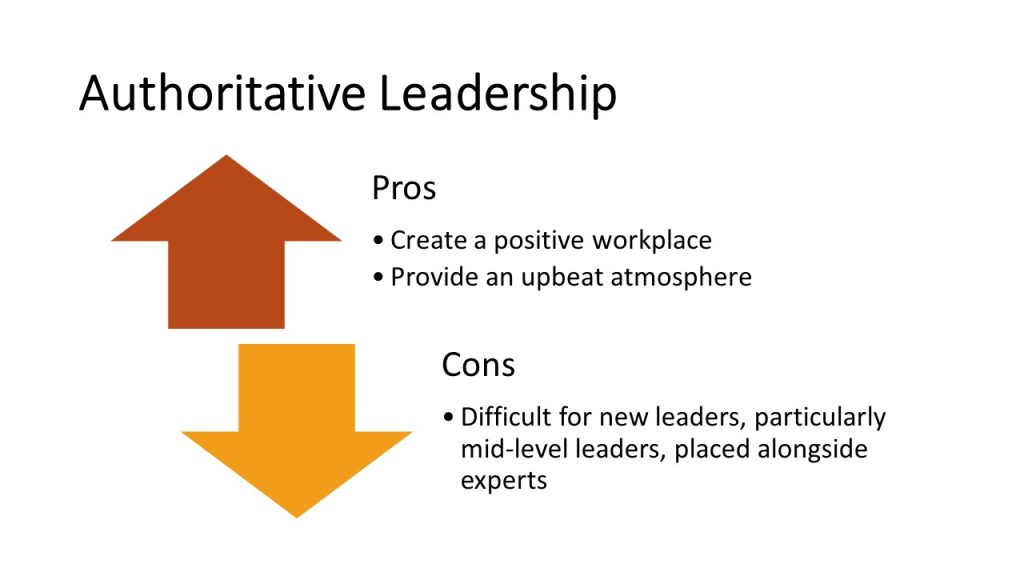

2. Authoritative Model of Leadership

Authoritative leaders set clear expectations on what needs to be done, and how it should be done. They believe they know more than their team members, thus leaving little to no time for group decision-making. These leaders usually have no time for touchy-feely team-building exercises and no time to waste seeking consensus or input from others. Can you think of an example of an authoritative leader, perhaps in the tech sector (Steve Jobs and his vision are often cited), or in your personal life? How far did their vision get them and their teams?

This method can be highly effective. However, if a new manager finds themselves placed into a workgroup of “experts,” it may be difficult, if not impossible, for this new leader to enter the group and immediately express their vision of where the workgroup should go. In addition, such a structure creates a strong division between leaders and followers, allows for little or no input from team members, and makes it difficult to transition to other leadership styles. Authoritarian leaders are often viewed as “bossy” and overly controlling.

Here is the modern 21st-century leadership model.

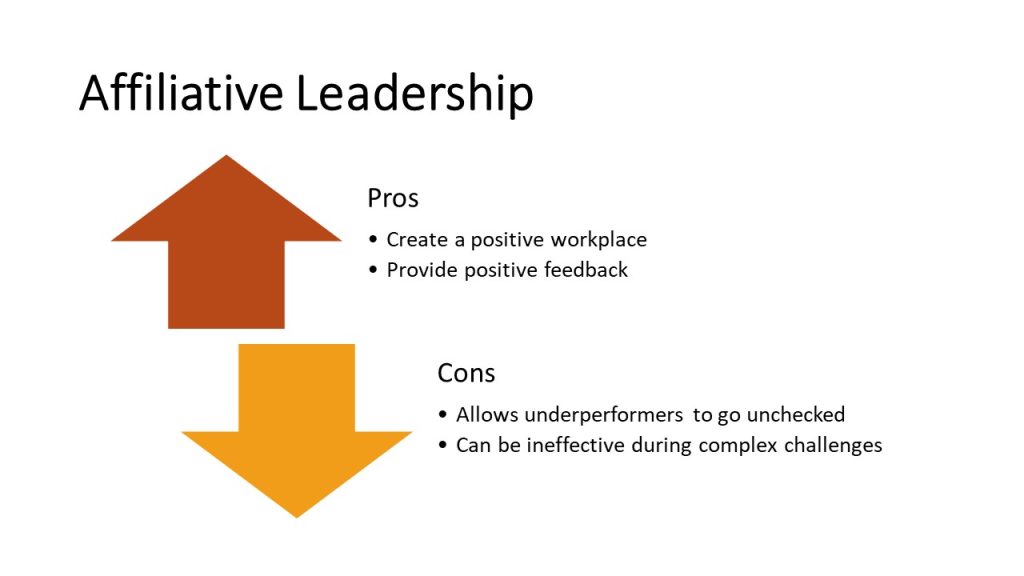

3. Affiliative Model of Leadership

The Affiliative model of leadership fosters connections, motivating team members not with threats or force but with praise and recognition. It puts the people in the organization first, attempting to build a collective identity. The classic example of an affiliative leader, and the one often cited by Goleman, is Joe Torre, the ex-manager of the New York Yankees. Consider for a moment the challenges faced by the manager of a professional baseball team, and the New York Yankees are not just any team. Joe Torre was the manager of one of the most talented teams in all of baseball. With all of that talent in one place, there are going to be many egos to consider as well. In this setting, perhaps one of the greatest accomplishments of a manager is simply holding the team together and building a sense of harmony among teammates. This is a skill that affiliative leaders master, and so has Joe Torre. Joe was quick to recognize the contributions of individual players and express his gratitude for the results in the Win/Loss columns. Examining his many positive statements in the press, and how well he treated his players, makes it easy to understand how effective an affiliative leader can be in the right setting.

There are, however, drawbacks to this leadership style. Poor performers may go unchecked, excessive positive encouragement may bring the bar down for the whole team, lackadaisical teammates may settle for mediocre performance, and the style may be ineffective during times of complex challenges. In addition, leaders of this sort may have difficulty providing honest feedback or exercising radical candor.

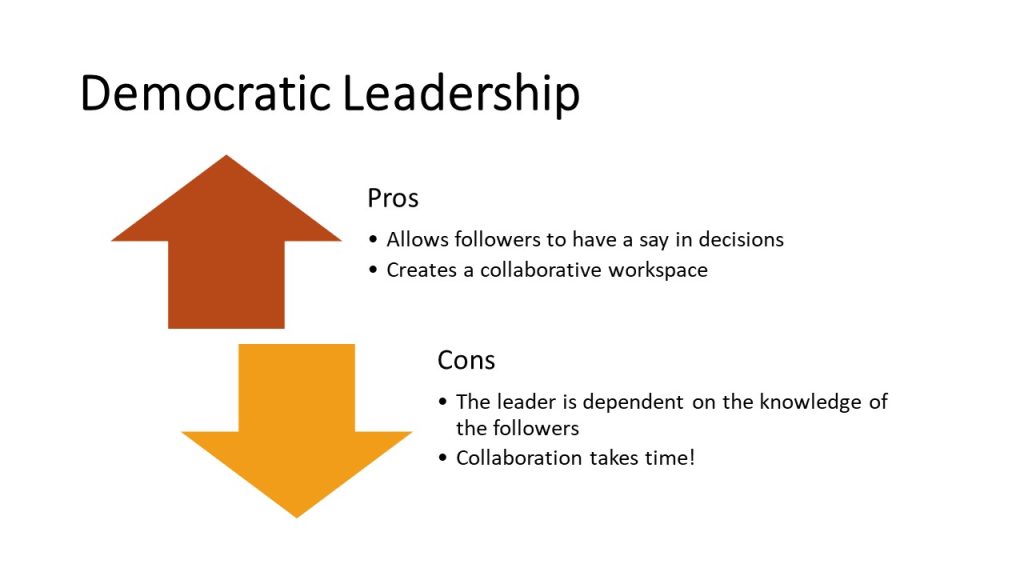

4. Democratic Model of Leadership

This management model is very participative. Management encourages power distribution while managers and employees actively take part in the decision-making process. Can you think of an example of this style of leadership? One often cited is Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who was able to mobilize an entire nation toward a vision.

While this is the preferred style for many modern leaders, this style can have negative consequences as well particularly for those without the dynamic personality of Dr. King! Every individual might expect their input to be valued and implemented, but in reality, only a few selected ones are implemented from a large pool of opinions. Thus, leaders spend lots of time collecting unused ideas, and then apologizing to those whose ideas were not used. Consensus approach can also lead to procrastination, while processing decisions is time-consuming (picture the endless meetings). This style can also introduce elements of uncertainty, as the leader might seem confused and without direction, particularly in critical situations that require an immediate response.

5. Pacesetting Model of Leadership

The pacesetting model requires the leader themselves to exemplify high-performance standards and ensure pace and structure within teams while matching their pace. In other words, the leader does not ask their team for anything they themselves are not doing. It involves strict deadlines and pressure on the team to develop faster workarounds. This style has great clarity of the requirements in place, which can be a significant advantage. It is also extremely efficient and results in quick bursts of high energy within the team, sometimes resulting in a frenzy of high-potential performance. A good example of this type of leadership is often said to be Jack Welch, the former CEO of GE.

In today’s modern workplace, this type of environment is sometimes referred to as “toxic” and “unempathetic.” Employees can easily feel overwhelmed by demands for excellence, resulting in a drop in morale. Teams can be consumed by demands and deadlines that suddenly drop on them or be denied holiday or weekend time off. This style likely does not conform to today’s corporate culture.

6. Coaching Model of Leadership

This is the least common style of leadership. It is characterized by partnership and collaboration, plentiful instruction, and teaching to employees. It is inspiring employees while building their confidence and providing support. It can result in fierce loyalty, as well as driven and satisfied employees. Long-term, it can mean a staff of highly competent individuals who are capable of multiple roles. A good example often cited is Mahatma Gandhi. He empowered a huge nation by getting the people motivated and believing in themselves.

In addition to the length of time the coaching style takes to be effective, it tends to fail if the employees are unwilling or incapable of learning, or if the leader does not quite have the best teaching skills in teaching making it frustrating and difficult for those trying to learn.

The New Innovative Model of Leadership

The above styles are typically what is taught and utilized. Today’s world, however, needs more innovative leaders. What does innovative leadership look like today?

It is the present and future that require radical collaboration. Picture a chromosome’s configuration. It is alive. A leadership model like this represents a fundamental paradigm shift from the hierarchical model.

It is not traditional, and it is not comfortable at first.

Leadership is not just a brilliant strategy coded into a complex machine. It is acting like the nervous system of an organism itself. To get there, leaders should start with some core questions. Great leadership, in fact, requires that leaders look within themselves and ask themselves some questions. There are three questions in particular: How to spend one’s time, whom to surround oneself with, and what ideas to explore.

1. Time

Yes, the question is about time. More specifically, how it is being spent. As a leader, what are you reading? What are you watching? Where are you traveling? Why does all of this matter? Because this is what defines one’s direction – it is where one looks to anticipate the next meaningful transformation.

2. Who

Leaders should always ask themselves: WHO is inside their trusted professional and personal circles? Diversity and inclusion are about justice and ethics. But they are also about innovation. Leaders should surround themselves with those who are different from them because they will innovate ideas based on their distinct backgrounds, experience, and mental processing.

Leaders should ask: “Am I surrounding myself with people who are and think differently than I do?” Because if they are not, they will inevitably be stuck in an echo-chamber that will stagnate their growth. Filling an office with others who look and think like one another might minimize office conflict and make it easier to spend time with these like-minded colleagues, but it will stifle innovation and meaningful growth.

3. Ideas

The leader has been successful so far and is now in a place of influence and control. But to live like a growing and evolving organism, leaders must discover the areas where past success will not equal future success.

In 2012, Google launched a team effectiveness study code named Project Aristotle. A tribute to Aristotle’s quote, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts” (as the Google researchers believed employees can do more working together than alone) – the goal was to answer one question: “What makes a team effective at Google?”

Google examined all of its various teams to see which ones were the most effective, then looked across a variety of factors to try to determine the reason behind that effectiveness. This is Google, so it stands to reason everyone is innovation-minded and intelligent. But what Google learned was the most effective teams always shared only one quality: an atmosphere of psychological safety.

Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson defines “Psychological Safety” as a “shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.” Psychological safety is “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up,” Edmondson wrote in a study published in 1999. “It describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves” (Edmondson, 1999).

In other words, good ideas come out of a space and atmosphere where bad ideas can be freely shared and exchanged.

In order to excel as tomorrow’s business leaders, leaders should consider moving from the strict hierarchical approach of top-down leadership, and move to the organic model of interaction, inclusion, and idea generation.

The Role of Global Business in Ethics, Diversity, Inclusion, and Social Change

The What and Why of Ethical Leadership

According to the Center for Ethical Leadership, “Ethical leadership is knowing your core values and having the courage to live them in all parts of your life in service of the common good.” Or, as it is sometimes stated, ethical leadership is “leadership demonstrating and promoting normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relations.”

In the past, ethical leadership was often cited as appropriate because it increases productivity and profits. In other words, there was always a numbers case made for ethical leadership. Indeed, there is an entire body of research in ethics and leadership finding that ethical leadership works to promote sustainability, increase output, and maximize empowerment, which in turn positively influences performance.

More recently, however, this model is criticized. Not because it is incorrect, but because it appears to ignore ethics as a good in and for itself. More modern ethical leadership models in the global business context stress integrity and dignity and other qualities that ensure standards of moral and ethical conduct. In other words, good leadership is no longer the motivational aspects of a business leader’s style to the extent they advance employee competence, but to the ethics themselves, and the ways in which those ethics transform organizations and the lives of the people within them.

A similar pattern has played out in the diversity and inclusion space. For most of the last twenty or so years, diversity experts would go into businesses, law firms, accounting firms, and conferences, discussing the profitability impact of diversity. The argument was that more and more businesses are owned by women and minorities, and more and more minorities and women have purchasing power, therefore operating a business in a manner that promotes those female and minority voices would positively influence profitability.

In the last few years, however, and in particular with the rise of the BLM and MeToo movements, organizations’ approaches to diversity and inclusion are much more morality based.

It is important to understand and internalize the truth that today’s leaders have power, and that power makes them responsible for including others to perform and act in a particular manner. They are in a position to influence processes and effect change in values, attitudes and actions, in the institutions in which they are leaders and, depending on what their business does, in society at large.

Acting in a manner that fosters trustworthiness and integrity is far more important to the values of an organization than whatever “values” statement leaders release on their corporate websites. Leaders can ask themselves who they want to promote, who should be in a position of power and leadership within the organization, and what message that sends. They may also ask themselves how those with little power in the organization ought to be treated, spoken to, or promoted. This trust will extend to loyalty, not just by employees, but also by vendors, partners, and ultimately, customers. The exact same is true for diversity and inclusion efforts.

It is also noteworthy that ethical leadership can prevent scandals, legal violations, lawsuits, and bad press. Leadership with ethics and ethical principles has significant short-term and long-term benefits for organizations and individuals alike.

How does one design an ethical workplace infrastructure that breeds integrity and fosters diversity, inclusion, and character?

Lots of organizations put in place a variety of compliance programs to accomplish this task. In fact, multinational enterprises are spending an average of $3.5 million per year on compliance programs. Often, however, these programs do not yield results. Ethical failures continue in all such corporations, inviting regulatory scrutiny, legal risk, reputational harm, and of course, that whole moral degradation thing that matters to the core of humanity.

Why do they fail? Well, they are often rooted in criminal law. That is, most corporations form compliance programs that view compliance from a criminal lens, asking employees and managers to avoid conduct that would have criminal legal implications. After all, there are now over 5,000 federal criminal statutes and 300,000 federal regulations, many of which are aimed at businesses. If a business’ entire compliance program is centered around avoiding illegal and criminal conduct, businesses, and the people within them, are incentivized to create an infrastructure that hides any illegal conduct. In addition, employees and managers end up rationalizing their unethical and illegal conduct – and avoiding the bad conduct becomes something that they do to avoid liability and less something they do just because it is the right thing to do. The reality is that even very well-intentioned people can be ethically malleable under the right set of circumstances, and the leader of the organization is ultimately the one responsible.

The panels of an ethical culture need to go far beyond simply avoiding audits by the IRS and investigations by the regulators. They include building an explicit values-driven culture – filled with principles that can be widely shared within the organization. Mission statements – only those that accurately reflect the leader’s vision and are frequently referenced during times of difficult decision-making –have been known to be effective. It may sound dull and cliché, but the right incentive can also help – incentive programs, such as programs that incentivize employees to tell the truth about an indiscretion from the very beginning of the act versus at some later point, or those providing a monetary or promotion and recognition-based value to character-driven and inclusive behavior, can make a big difference in compliance. This could be as simple as an employee of the month award, voted on by others in the office.

Cultural norms will always be key. Leaders must establish the norm at the top. Leaders want their employees to create a culture of psychological safety that fosters diverse voices amongst themselves, then set that standard at the officer, director, and manager levels. Social norms are incredibly powerful, and leaders can demonstrate ethical norms through hiring trends, promotions, evaluations, and compensation.

Neither individuals nor corporations can be perfect. But by examining one’s leadership skills to optimize performance while valuing ethics, and including diversity and inclusion, leaders not only significantly increase productivity, but they benefit from feeling and being a better person, one whose leadership inspired others to have a positive impact in a business, an industry, and perhaps even the world.

Bibliography

Edmondson, 1999

Edmondson, Amy. “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams.” Administrative Science Quarterly 44, no. 2 (June 1999): 350-83. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999.