Macro-Global Economic Environment

Shermin Kruse

What are the basic principles of international trade? What are trade restrictions, and how do they function? What is free trade, and what is its purpose? What are trade blocks? What are the world's global economic institutions? How does the World Trade Organization function? What is the International Monetary Fund? How about the World Bank? How do these institutions interrelate with one another or impact multinational enterprises? This chapter provides a basic sketch of the macroeconomic environment that affects and is affected by global businesses.

Basics of Trade Restrictions

All governments restrict foreign trade for the same basic principle: to protect domestic producers from foreign competition. Thus, while there are various trade barriers put in place, they all more or less accomplish the same thing: place some kind of cost on foreign-produced goods, thus somehow promoting domestically produced goods. Free trade, then, is the lifting of those barriers.

- Tariffs are excise taxes on imports and are used to generate revenue.

- Import Licenses are permits to import a certain amount of a certain good over a specified period (typically one year). Requiring such licenses limits the outflow of foreign currency while strengthening the domestic economy.

- Export licenses are documents allowing registered corporations to ship restricted goods (such as chemicals, medicines, artwork, historical artifacts, and dual-use items).

- Import quotas are regulations that limit the amounts of imports allowed in a certain period of time. Some economists believe that low import quotas may be a more effective protective device than tariffs because tariffs do not limit the number of goods entering a country but simply make it more expensive to engage in the import.

- Trade subsidies are specifically defined under the Subsidies Agreement and U.S. law (Title VII of the Tariff Act of 1930) as a "financial contribution" by a government that provides a benefit. They can be a direct transfer of funds or liabilities (such as grants, loans, or loan guarantees), foregone government revenues (such as tax credits), or the purchase of goods.

- Voluntary export restrictions are agreements by a government to voluntarily limit their exports to a particular country (rather than a tariff on an import), so it is not a restrictive trade barrier.

- Local Content Requirements are government-imposed rules that require companies to use domestically manufactured goods or services to operate within a particular economy. These methods of advancing domestic products and services is increasingly popular in recent years.

- Embargos or sanctions are trade restrictions imposed as a political measure to apply pressure on foreign governments but nevertheless have a significant economic impact. Embargos are complete bans of trade from one country to another, whereas sanctions are trade prohibitions on particular products, services, or technologies.

- Currency devaluation is the implementation of strategies intended to cause a downward adjustment of the value of a country's currency relative to another currency (or a group of currencies, or currency standards). For example, a country may choose to take such an action to gain a competitive edge in global trade or reduce the sovereign debt because a weak currency makes that nation's exports more competitive in a global market while simultaneously making imports more expensive.

- Non-tariff barriers can refer to any number of intangible trade impediments, such as unreasonable standards or bureaucratic red tape in customs procedures.

Governments place trade restrictions on particular foreign goods for a variety of reasons. There are several main justifications offered.

First, governments often claim they are placing trade barriers to increase domestic jobs. Trade barriers do, in fact, have the impact of protecting some domestic industries from foreign competition. Often these are placed on incoming foreign goods to drive up the demand for domestically produced goods, which in turn increases domestic jobs. Because the external factor of imposing trade restrictions on a particular good decreases foreign competition for that good, they necessarily drive up the price of that good within the domestic market. Therefore, trade barriers may increase domestic jobs for manufacturing the restricted product, but they also increase the cost of that product to domestic users and consumers. These higher prices could also result in a decrease in the consumption of the good in question, which could ultimately reduce jobs in the industry as fewer goods would be made.

For example, assume the product is steel, and the United States government places tariffs on the foreign import of steel. This tariff drives up the price of foreign steel, making it easier for domestic steel manufacturers to compete. A tariff on a particular product might increase jobs within that specific industry, tariffs have an overall adverse effect on jobs in the economy. If the price of domestic steel goes up, this also increases the price of steel to United States consumers and any other United States industry that uses steel in the products they manufacture. Steel makes up railroads, vehicles, oil and gas pipelines, skyscrapers, elevators, subways, bridges, automobiles, ships, knives and forks, razors, surgical instruments, and many other products. If a trade restriction raises the domestic price for steel, the price of any product that uses steel as a component part also increases. Therefore, if the price of steel goes up, so does the price of vehicles, which adversely affects the profitability of the automotive industry, thus negatively affecting employment possibilities within that market.

Proponents of trade restrictions offer other reasons to justify the restrictions besides additional jobs. Many proponents of trade restrictions argue the restrictions must be put into place to "level the playing field" and create more fair competition. In some cases, this argument is accurate, such as when foreign producers receive unfair advantages (subsidies or an intentionally devalued currency from their own government). If the foreign producer has some sort of unfair advantage, then a trade restriction placed on that good by our government would be an effort to make the marketplace more "fair" for that particular good. This analysis is often complex and requires an evaluation of whether the foreign producer has an advantage and whether that advantage is "fair," a term that is subjective and difficult to analyze objectively.

A third justification for using trade restrictions is that they raise revenue for the governments imposing them. After all, the tariffs and revenues from quota licenses are paid to the nation's government that is imposing those restrictions, so they are a tax on the foreign good paid to the government. This argument is not very compelling for wealthy countries such as the United States, where the majority of the government income is derived from personal and corporate income taxes and a very small percentage of the revenue is derived from foreign sellers of goods. It can, however, be a very compelling argument for governments of developing and economically struggling nations because they have much less local income to tax and can raise their tax revenues substantially by taxing foreign producers. Note, though, that in the case of any country that imposes trade restrictions, government tariff revenue represents a transfer of income from consumers to their government, which is not necessarily a good result.

Another argument often raised in favor of trade restrictions applies to particular industries that are critical to national defense. The idea is that if there is a particular industry that is critical to our nation's domestic security and would be placed under strain in times of war, the nation should protect that industry during peacetime to ensure, from a domestic security point of view, it is stable should war arise. Suppose the United States finds itself amidst another war. What industries would be essential to maintaining its strength amidst that conflict, or more candidly, what industries create the raw materials necessary for modern-day weaponry? Steel once again comes to mind. The argument becomes problematic when one begins to question the premise of what is "necessary" during times of war. In other words, while steel might be necessary to build weaponry, access to food, or clothing, would also be affected in case of significant conflict. Therefore, the argument could be made that nearly any American industry would need protection during times of conflict and therefore should receive protection from foreign competitors in the form of trade restrictions. In recent years, the argument has been broadened from critical to the "national defense" to critical to the "national interest," which according to the interpretation of some countries, includes moral and cultural protection issues.

A fifth justification for trade restrictions is that they should be put in place for new industries so they are protected until they are in a better position to compete with foreign distributors on their own two feet. This "infant industries" argument is similar in theory to building an incubator for these industries. The concern with this argument is that it is unclear when the new industries no longer deserve external protection. In the United States, this issue was addressed by the International Trade Center, which places objective time limits on trade restrictions for infant industries.

In short, there are many arguments and counterarguments as to why countries might protect domestic producers through the imposition of trade restrictions. Economists are generally supportive of free trade and view economic protectionism as having an adverse impact on nations' economic growth and welfare. There are, however, economists who believe free trade only favors wealthier nations and is very harmful to developing economies, some even saying it forms the basis of poor working conditions and degradation of natural resources in developing countries.

The World Trade Organization

GATTs, superseded by the World Trade Organization, is essentially a durable code of conduct that is established for global commercial policy and international dispute resolution. It implements mechanisms to lower tariffs significantly, so as to advance and increase free trade as much as possible. To that end, it also has mechanisms in place to diffuse potential trade wars, which are nearly universally understood to be bad for all the countries involved.

The World Trade Organization is also dedicated to expanding trade between developing nations. One of the ways in which it does that is by persuading developed nations to tone down tariffs on developing nations and attempting to bring down barriers to free trade.

We now turn to the World Trade Organization's dispute and settlement system to understand how trade-related conflicts are resolved at the WTO.

In 2018, President Trump decided to impose tariffs of $247 billion on Chinese goods, among the most severe economic restrictions ever imposed by a United States president. These tariffs were to apply to more than 1,000 products, ranging from air conditioners to iPhone chargers. Remember that tariffs are paid by United States companies that import the products, and of course, they often pass the cost along to U.S. consumers. For this reason, American companies were, by and large, afraid of the impact these tariffs would have on the cost of consumer goods, particularly since the bulk of them were announced in September of 2018, just before the holiday season. For example, Apple expressed concerns that, "The burden of the proposed tariffs will fall much more heavily on the United States than on China."

In response to these tariffs, the Chinese launched a complaint at the WTO, claiming that the United States violated United States commitments under global trading rules with the new tariffs.

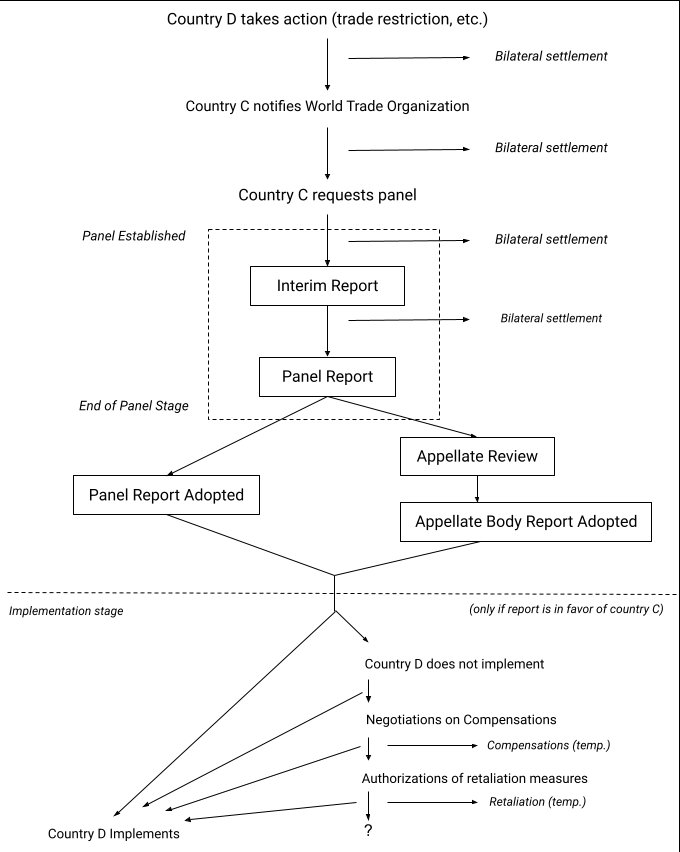

The above chart outlines the process nicely. Country B in this chart is the country that has filed a claim with the World Trade Organization alleging an illegal trade restriction, such as an illegal tariff. Country A is the accused country, the one who has allegedly imposed the illegal tariff.

Step 1 is Country A taking action – imposing the trade restriction. Country A then notifies the World Trade Organization. Note, as evident from the chart, that there is an opportunity both before and after that claim is filed for the two countries to settle the matter – a bilateral settlement as it is described here. If none is reached, Country B requests a panel of judges to determine the dispute.

Panels are the quasi-judicial bodies that serve as tribunals. They are responsible for adjudicating disputes between Members in the first instance. They are composed of three (sometimes five) experts selected on an ad hoc basis. Thus, there is no permanent panel at the World Trade Organization; instead, a different panel is composed for each dispute.

Once the panel is established, there is yet another opportunity to resolve the matter through a bilateral settlement. If that does not happen, the panel hears the case and drafts an interim report of what their opinion will be. Here is yet another opportunity to settle. If there is no settlement, the panel issues its report. Assuming the aggrieved party determines to continue the process, the parties enter the appellate process. Finally, after the appellate review, the panel's opinion is either adopted, or the appellate body issues its own report, presumably different than the panel report, which is then adopted.

Suppose the ultimate ruling is in favor of country B (the country that brought the action alleging an unfair trade restriction). In that case, this means Country A is found guilty of the allegations and must make a change by implementing the findings of the panel. This could mean everything from easing to eliminating the trade restrictions and could include a monetary award component as well.

Country A now has some decisions to make. It can implement the appellate body report, or it can refuse to do so. If it refuses, it can try to negotiate with Country B – in other words, yet another settlement opportunity, or it can retaliate through lawsuits of its own.

The process, therefore, is lengthy and slow, mostly intended to provide the countries with an opportunity to resolve the matter through settlement.

The table below guides the approximately length of time consumed by each phase of dispute resolution at the WTO level. Essentially, even without an appeal, it can take over a year for the process to result in a decision.

Time Frame of the Conflict Resolution Process

| Time | Step |

|---|---|

| 60 Days | Consultations, mediation, Etc. |

| 45 Days | Panel set up and panelists appointed |

| 6 Months | Final panel reports to parties |

| 3 Weeks | Final panel report to WTO members |

| 60 Days | Dispute Settlement Body adopts report (if no appeal) |

| Total = One Year | (Without Appeal) |

| 60-90 Days | Appeals report |

| 30 Days | Dispute Settlement Body adopts report |

| Total = 1 Year + 3 Months | With appeal |

Returning to the example of President Trump’s tariffs: It took until September 2020 for the WTO to reach a decision. On September 15, 2020, a three-member WTO panel struck at the core of Trump’s trade war with China, ruling in favor of China and holding that the United States violated global trading rules.

What is the effect of this ruling? What happens now? What is the enforcement mechanism? It has not even gone through an appeal yet. But the question can still be answered as follows:

The main enforcement mechanism is our desire to continue to engage in global trade and bilateral as well as multi-lateral transactions across borders. Ignoring international trading rules and rulings of the WTO is very bad for American business. Realistically, this fact, in and of itself, is the core of the enforceability of WTO rules – essentially, the consequences of refusing to comply are too dire from a trade point of view.

In fact, only a few hours after the ruling, the Trump administration suddenly announced it was abandoning tariffs on aluminum from Canada that the President had imposed just one month prior.

Interestingly, in January of 2022, the WTO granted Beijing a new tariff weapon against the U.S., relating to a separate and older dispute. It ruled that China can retaliate against $645 million worth of annual American exports as part of a decade-old trade dispute over U.S. anti-subsidy duties on Chinese goods. This ruling came at a time of great political sensitivity for the new Biden administration and nearly one year after a shaky “truce” of sorts in the trade war between the two countries. $645 million is much less than the $2.4 billion that China had initially requested in that dispute, and pales in comparison to the tariffs China imposed on $110 billion worth of U.S. goods during the Trump administration. Nevertheless, it is a significant amount in both monetary, diplomatic, and political terms.

IMF and the World Bank

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank are interrelated finance arms of the U.N. The World Bank focuses on financing and investing in developing companies and eliminating poverty, while the IMF primarily monitors exchange ranges, stabilizes international money systems, and fosters global financial cooperation.

The World Bank

Together, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Development Association (IDA) form the World Bank, which provides financing, policy advice, and technical assistance to governments of developing countries. IDA focuses on the world's poorest countries, while IBRD assists middle-income and creditworthy poorer countries.

The Five Institutions of the Word Bank

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

- International Development Association

- International Finance Corporation

- Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency

- International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes

The World Bank's mission is to fight poverty and inequality by offering money and advice to developing countries. It was first developed in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in the year 1944, at the same conference which saw the conception of the International Monetary Fund. However, while the IMG tackles acute crises such as capital flight, sudden dollar shortages and currency misalignments, the World Bank's goals are to battle chronic long-term problems of deprivation and backwardness. Part of the World Bank's original mission included, for instance, the rebuilding of Europe's war-blasted infrastructure, and its first loan was to France.

According to its website, “[T]he World Bank is a vital source of financial and technical assistance to developing countries around the world. We are not a bank in the ordinary sense but a unique partnership to reduce poverty and support development. The World Bank Group comprises five institutions managed by their member countries.” It is headquartered right here in the United States, more specifically in Washington DC, and has more than 10,000 employees and 120 offices worldwide.

In addition, according to its website, the World Bank has two main goals, which it aims to achieve by the year 2030:

- End extreme poverty by decreasing the percentage of people living on less than $1.90 a day to no more than 3%.

- Promote shared prosperity by fostering the income growth of the bottom 40% of every country.

This is the stated purpose, but underlying this purpose is the undeniable fact that the impact participation by developed countries in the World Bank has on their overall power and control of macro-global economic systems, as well as the economic systems of borrowing countries.

The United States holds approximately 16% of shares in the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, with 14.97% of the voting power. It holds 10.46% of the voting power in the International Development Association, the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries. Consider the power that the United States has, even when it comes to the internal affairs of lending countries, it takes much less time to execute cross-border transactions related laws and rules.

Recent Examples of World Bank Activity

World Bank and Guyana:

Guyana is amongst one of the poorest countries in South America and the World Bank declared that Guyana must improve its quality of infrastructure. The World Bank has loaned $61 million to Guyana across four areas: education, energy, flood risk management, and the financial sector (World Bank Group 2020a). The most recent loan to Guyana was in support of its flood risk management project, reducing the impact of natural disasters on Guyana's citizens and their economic activity. In November 2020, the World Bank approved a $26 million loan towards Guyana's flood risk management project.

“Ninety percent of Guyana’s inhabitants live on the narrow coastal plain, much of which lies below sea level. Flooding poses a serious and recurrent risk to both the lives of people and to livelihoods in the agricultural sector. These additional resources will help protect some of the country’s most populous areas and build greater resilience,” said Ozan Sevimli, World Bank Resident Representative for Jamaica and Guyana (McLeod 2020).

World Bank and Tanzania:

In 2018, the World Bank delayed a planned $300 million educational loan to Tanzania after the country implemented a policy that expelled pregnant girls from school. Although the practice of testing school girls for pregnancy dates back to the 1960s, the law to require schools to test for pregnancy and subsequently ban pregnant girls from school became more widely applied since President John Pombe Magufuli took office in 2015 (Kottasová 2018a). The $300 million loan from the World Bank was intended to help Tanzania’s Ministry of Education improve its quality and access to secondary education. As activists, such as the US-based Center for Reproductive Rights, put forward statistics that over eight thousand pregnant girls were being expelled and/or dropped out of school every year, Tanzania imposed a new statistics law that made it illegal to question official statistics. Following this law, the World Bank withdrew their loan and suspended all visiting missions to Tanzania (Kottasová 2018b). In 2019, Tanzania amended its statistics law which reversed its criminal implication effects (Nyeko 2020).

"The economic and social returns to girls finishing their education are very high in every society for both current and future generations. Working with other partners, the World Bank will continue to advocate for girls' access to education through our dialogue with the Tanzanian government," an official statement from the World Bank in 2018 (Kottasová 2018b).

In defense of President Magufuli’s guidelines, proponents of the rule state that it allows girls to focus on their education and avoid pre-marital sex, and that there is no law preventing the girls from attending private school online.

"In my administration as the President no pregnant girl will go back to school... she has chosen that of kind life, let her take care of the child," President John Pombe Magufuli said at a public rally in 2017 (Kottasová 2018a). His speech removed any discretion schools had over how they enforced the morality rule.

Two years later, in January 2020, the executive board of the World Bank was set to meet to reconsider the loan to Tanzania. However, activists called on the World Bank to postpone any educational loans to Tanzania until the country passes a law that grants the rights of pregnant girls to attend school. Finally, the meeting was postponed and consideration for the loan delayed (Kottasová 2020).

However, in March 2020, the World Bank finally approved a $500 million load to Tanzania for its secondary education program. Activists and human rights organizations heavily criticized this (Ng’wanakilala 2020).

Note: This is one example of the contrast between the AIIB and the World Bank. The promise of no-strings-attached infrastructure financing of the AIIB compared to the World Bank withholding a loan due to a country's policy with which it does not agree.

World Bank and Lebanon:

In August of 2020, amid the Covid-19 pandemic, a large amount of ammonium nitrate unsafely stored at the port in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, exploded and caused 204 deaths and around 6,500 injuries. In addition, due to property damage from the explosion, approximately 300,000 people were left homeless (WHO 2022). Lebanon’s financial and economic crisis tipped in October 2019 due to various factors, and the explosion coupled with the Covid-19 pandemic worsened Lebanon’s already suffering financial crisis. In December of 2020, the World Bank warned that Lebanon’s economy will continue to shrink and more than half of the population is expected to fall into poverty by the end of 2021 (Al Jazeera 2020). On December 4th 2020, exactly four months after the deadly explosion in Beirut, the E.U., U.N., and the World Bank launched a "18-month Reform, Recovery and Reconstruction Framework (3RF)" in response to the Beirut Port explosion to help Lebanon's economic recovery and reconstruction (World Bank 2020).

“As things stand, Lebanon’s economic crisis is likely to be both deeper and longer than most economic crises,” World Bank economists warned in their Lebanon Economic Monitor report titled The Deliberate Depression. (Al Jazeera 2020).

International Monetary Fund

What is the IMF? According to its website, “The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is an organization of 189 countries, working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world.”

The agenda of the IMF is focused on 3 Primary Tasks:

- Surveillance. The IMF is responsible for monitoring financial and economic activities to develop policies and strategies and recommendations for proactive crisis prevention. Therefore, they monitor all global financial and economic activities. For example, the IMF monitors the activities here in the United States, while also monitoring the economic activities in Greece, Iran, Kenya, etc., then uses that information to develop policies and strategies so that they can try to figure out how to prevent a crisis from happening, such as the collapse of the Euro.

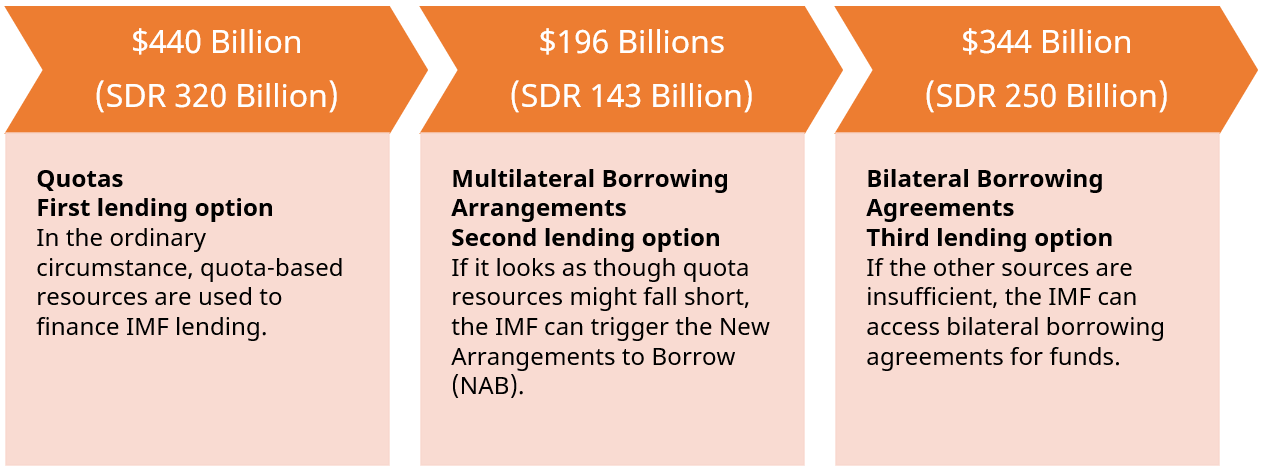

- Lending. The IMF provides funding for short-term, low-interest loans for macroeconomic issues related to political and& economic stability. Note that the IMF only lends to governments, not the private sector or civil society. Furthermore, all IMF financing is fungible, meaning the loan itself is not tied to any specific project or expenditure, unlike loans by development banks that are often used to support specific projects. Almost all IMF loans come with stringent conditions related to policy changes that governments are required to make to receive the funding. The main purpose of these loans is to distribute them to countries facing difficulty with their payment balances, provide temporary financing where it is needed, and support policies aimed at correcting the country's underlying fiscal problems. Note that loans to low-income countries are also aimed especially at poverty reduction.

- Technical Assistance. The IMF provides training and consultation for loan applications, policy reforms, and the interpretation of data. Technical assistance helps countries develop more effective institutions, legal frameworks, and policies to promote economic stability and inclusive growth. Training through practical policy-oriented courses, hands-on workshops, and seminars strengthens officials’ capacity to analyze economic developments and formulate and implement effective policies.

It was established in 1944, is headquartered in Washington, DC, and it has 190 member countries. It has an Executive Board that is comprised of 24 Directors each representing a single country or groups of countries. Just the staff of the IMF alone represents the nationalities of approximately 150 different countries. It provides surveillance and technical assistance, policy-oriented training, and peer learning worth $330 million. Of course, it also lends money. The total amount the IMF can lend to member countries is one trillion dollars.

In 2008, the IMF also began making loans to countries hit by the global financial crisis. The IMF currently has programs with more than 50 countries around the world and has committed more than $325 billion in resources to its member countries since the start of the global financial crisis. During the Covid pandemic, the IMF provided emergency financing to 76 different countries. Sometimes, countries qualify for and receive a 0% interest rate on their loans. In addition, some low-income countries are also eligible for debts to be written off under two key initiatives.

Finally, further discussion is merited regarding the ownership percentage of the IMF.

| Member | Quota (Millions, SDR) | Quota Share (%) | Vote | Vote Share (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 82994.2 | 17.46 | 831407 | 16.52 |

| Japan | 30820.5 | 6.48 | 309670 | 6.15 |

| China | 30482.9 | 6.41 | 306294 | 6.09 |

| Germany | 26634.4 | 5.6 | 267809 | 5.32 |

| France | 20155.1 | 4.24 | 203016 | 4.03 |

| United Kingdom | 20155.1 | 4.24 | 203016 | 4.03 |

| Italy | 15070 | 3.17 | 152165 | 3.02 |

| India | 13114.4 | 2.76 | 132609 | 2.64 |

| Russian Federation | 12903.7 | 2.71 | 130502 | 2.59 |

| Brazil | 11042 | 2.32 | 111885 | 2.22 |

Note the significant quota share and vote share of the United States, which informs significantly regarding the power of the United States in international affairs. In addition, it stands to reason the United States' position as by far the highest controlling interest in the IMF and the World Bank, provides it with a substantial impact on foreign policy, negotiating power, trade deals, economic bargains, travel restrictions, and other international trade and security-related issues. This imbalance of power has motivated other countries, particularly China and Russia, to increase their global power through macro-global economic participation.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) Examples:

Financial Collapse of Greece, International Monetary Fund and Effects on the European Union:

In 2001, Greece was admitted into the Eurozone and incorporated the Euro as a national currency. Greece struggled with deficit and debt and falsified its good financial standing to successfully join the Eurozone, hoping that its transition would boost the economy (Carassava 2004). After the transition, many investors and banks immediately invested in Greece.

The financial crisis of Greece resulted mostly from structural issues and systematic tax evasion. It was a social norm for self-employed wealthy workers to under-report income while over reporting debt payments. In addition, Eurozone membership allowed the Greek government to borrow at a low rate in the absence of sufficient tax revenues. However, Greece had a very low productivity rate compared to its European Union counterparts which made Greek services and goods less competitive (Johnston 2021).

In 2007, The Global Financial Crisis weakened Greece's tax revenues which worsened its deficit. In 2010, the IMF, along with the ECB (European Central Bank), bailed out Greece under the IMF's terms and conditions. These conditions required the Greek government to impose higher personal income taxation and government spending cuts, resulting in the loss of thousands of government jobs (BBC News 2010). Greece's economy continued to struggle, and over the years, with each following bailout, the terms and conditions imposed by the International Monetary Fund extended. Some economists criticize the International Monetary Fund, stating that forcing a tough austerity on Greece further strangled its economy.

In opposition to the International Monetary Fund's bailout conditions and extensions of austerity measures, citizens protested, and riots erupted in the streets of Greece. In Greece, public opinion turned against the European Union and stirred nationalist sentiments (Zettelmeyer, et al. 2021).

In 2015, a new left-wing Syriza government led by Alexis Tsipras was elected and then began criticizing the European Union and demanding less restraint over Greece’s economy (Council on Foreign Relations 2022). The Eurogroup (informal body where the ministers of the euro area member states discuss matters relating to their shared responsibilities related to the Euro) (European Council 2022). refused. The world watched closely as the European Union appeared to be on the brink of a fall-out and large speculation of a Greek exit from the European Union. “The confrontation rekindled a crisis.” (Zettelmeyer, et al. 2021). Greece and the European Union ultimately compromised a new reform program and Greece remained as a member of the European Union (European Council 2022).

By 2015, Greece’s missed payment of 1.6 billion euros to the International Monetary Fund (International Monetary Fund) was the first of its kind, it was the first time a developed nation had missed so much (Council on Foreign Relations 2022).

In 2018, Greece received in final loan and exited the bailout program, in debt to the European Union and International Monetary Fund by approximately 290 billion euros. The European Union hailed the Greek exit of the bailout program and return to growth as a success. However, the International Monetary Fund warned that Greece will likely need further debt relief in the future (Council on Foreign Relations 2022).

By January of 2020, Greece had concluded the early repayments of its International Monetary Fund loans, which amounted to about 2.7 billion euros (Reuters 2019). Since Greece's finances improved, the International Monetary Fund is set to close its office in Greece so the country could emerge from International Monetary Fund's supervision and framework, although the European Union would continue to observe and monitor the country's fiscal matters (Reuters 2020). Due to the Covid-19 Pandemic, Greece’s modest economic recovery was interrupted (OECD 2020). The country and the European Union feared a relapse. A report by the International Monetary Fund in November of 2020, however, stated that Greece's fiscal response to the pandemic has been "well-organized and has mitigated impact" and its public debt is currently sustainable, although its long-term sustainability and economic recovery is not guaranteed (IMF 2020).

Long-term Impact from Greek EU-International Monetary Fund bailout on the E.U.:

As a direct response to prevent a future financial collapse similar to Greece's, in 2012, European leaders gathered at a summit in Brussels to create The Treaty Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic Monetary Union (TSCG). Otherwise known as The Fiscal Compact Treaty, this treaty mandates stricter budget discipline throughout the European Union. The TSCG includes a budget rule requiring governments to maintain deficits below 0.5% of GDP and an undefined correction mechanism for countries that do not meet the target. 25 European leaders signed the treaty, all but the U.K. and the Czech Republic (Council on Foreign Relations 2022). The Fiscal Compact Treaty went into effect on January 1, 2013 and remains in place today (Dullien 2012).

The contradictory stereotypes surrounding Greeks during their financial crisis was evident, and these stereotypes remain alive today. According to surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center from 2012-2014, Greeks saw themselves as the most hardworking Europeans while the British, Germans, Spanish, and the Czechs saw Greeks as the least hardworking Europeans. Greeks viewed themselves as the most trustworthy Europeans, while the Germans, French, and Czechs viewed Greek citizens as the least trustworthy. Only 17% of Greeks agreed that European Union economic integration had been good for their country. In addition, 85% of Greeks agreed with the sentiment that the European Union does not understand their needs (Stokes 2020).

International Monetary Fund and Covid-19 Aid relief:

- The Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT) was established in 2015 after the Ebola outbreak. The CCRT allows the International Monetary Fund to lend money for debt relief to vulnerable countries affected by catastrophic natural or health disasters. According to the International Monetary Fund, the purpose of the CCRT is to "free up resources to meet exceptional balance of payment needs created by the disaster rather than having to assign those resources to debt service” (IMF 2021). However, some warn that the International Monetary Fund is encouraging countries to spend as needed, which will ultimately result in those countries being indebted to the International Monetary Fund for many decades (Oxfam International 2020).

- As a direct result of the Covid-19 Pandemic, the lack of tourism has punished the economy of developing countries (Goodman 2020). In April of 2020, the International Monetary Fund warned that immediate and immense relief was required to prevent both significant damage to global prosperity and a humanitarian catastrophe (IMF 2020). In response to the Covid-19 Pandemic, the International Monetary Fund has made $250 billion, a quarter of its $1 trillion lending capacity, available to eligible countries (IMF 2022). The International Monetary Fund also enacted a Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) which temporarily suspended debt service payments from the poorest countries that request it to temporarily ease the financing constraints (IMF 2022b).

- By accepting the funds from the International Monetary Fund, borrowing countries agree to the IMF's terms and conditions, which sometimes require countries to increase income taxes and make major cuts to national spending, potentially causing deep cuts to pensions, wages, healthcare systems, and public sector workers.

- In October of 2020, over 500 organizations, including the ACTION Global Health Partnership and International Federation for Human Rights, sent a letter to the International Monetary Fund calling for the end of required austerity measures and warning that Covid-19 relief financial aid from the International Monetary Fund will condemn “many countries to years of austerity.”

Direct Quotes from the letter to the International Monetary Fund (Oxfam International 2020):

“International Monetary Fund loan programs — and the conditions that accompany them — will play a highly influential role in shaping the economic and social landscape in the aftermath of this pandemic.”

“The undersigned, call on the International Monetary Fund to immediately stop promoting austerity around the world, and instead advocate policies that advance gender justice, reduce inequality, and decisively put people and planet first.”

Chomsky’s Views and International Monetary Fund:

Noam Chomsky is an American linguist, philosopher, and historian whose controversial views and opinions of the International Monetary Fund rose to popularity in the late Twentieth-century (Milne 2009). According to Chomsky, there is a substantial gap in interest between the public and those who control American foreign policy. Chomsky states that the mass population bears the burden of repayment and debt to the International Monetary Fund, not those who made the bad loans, such as the banks or economic elites. Chomsky claims that the International Monetary Fund has strayed from its original function and now serves as the world’s credit community’s enforcer, which results in grim effects in developing nations. Chomsky believes that debt is merely a social and ideological construct, not an economic fact, and debt serves as a vehicle for the rich and powerful to maintain control and power over the mass population. The reason is that in the past, world leaders cancelled debt only when it benefits the elite and powerful. The International Monetary Fund has been, at times, criticized by social-activists and world charities for its austerity over nations to which it lends money to and for being pro-Western at the expense of Third World countries.

“The logic extends readily to much of today's debt: 'odious debt' with no legal or moral standing, imposed upon people without their consent, often serving to repress them and enrich their masters.” – Noam Chomsky. (Guardian 1999).

Responses to the World Bank – New Development Bank (NDB) and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)

Many countries are looking at the growing power of the United States with concern. They seek some sort of counterpart to the International Monetary Fund and the resulting United States’ global dominance. The two primary results are the New Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (or the AIIB). Both are multilateral development banks; essentially global financial institutions backed by governments to provide long-term finance for sustainable infrastructure such as roads, rail, ports, power, and telecommunications. Such infrastructure financing is typically accomplished through loans, equity, guarantees, and other financial instruments.

New Development Bank

The BRICS countries formed the New Development Bank. BRICS is a grouping acronym referring to Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. These countries are developing nations at a similar stage of newly advanced economic development, on their way to becoming developed countries. The member states collect to discuss finance, trade, health, communication, labor, and issues relating to economics and security. The goal is for the BRICS countries to constantly interact and develop each other’s economies.

Significantly, 43% of the world population resides in these five countries, with 30% of the world GDP, and 17% of all trade controlled by BRICS countries. These five countries are also part of the G20 summit. At the 2015 BRICS summit, there was a decision to create the New Development Bank to support public and private projects through loans, equity, and other debt instruments (proposed by India). This plan became a reality at the 7th BRICS summit in 2015. Its first annual meeting took place in 2016.

The Mission of the New Development Bank

“The Bank shall support public or private projects through loans, guarantees, equity participation and other financial instruments.” Moreover, the New Development Bank has stated that it "shall cooperate with international organizations and other financial entities and provide technical assistance for projects to be supported by the Bank." At the core of the New Development Bank is sustainable infrastructure development, with a priority to developing renewable energy sources and innovation.

It is headquartered in Shanghai, China, and its first regional office was built in Johannesburg, South. Africa. From its founding, the New Development Bank board of governors was clear that expansion of membership beyond the founding members was a strategic focus of the bank designed to extend its reach and development impact across the BRICS countries and other emerging markets and developing economies. In 2017, the governance board of the New Development Bank approved the terms, conditions, and procedures for the admission of new members. Afghanistan, Argentina, Indonesia, Pakistan, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Nigeria, Sudan, Syria, Bangladesh, Greece, and others have expressed an interest in full membership.

The initial authorized capital of the bank is $100 billion divided into 1 million shares having a par value of $100,000 each. While this might seem like a substantial sum, recall that the United States contribution to the International Monetary Fund is $150 billion. Therefore, the New Development Bank still has quite a way to go before it can catch up to the impact and influence of the International Monetary Fund. Still, the New Development Bank attempts and is in some measure succeeding, in counteracting the influence of the United States in the global economic lending space.

New Development Bank and Covid-19:

- The New Development Bank is focusing its Covid-19 pandemic relief efforts on its member countries. BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) are some of the worst hit by the pandemic. Some claim that the New Development Bank's involvement during the pandemic validates its existence and creation and that it cemented its place as one of the most critical sources of external financing for BRICS countries. The New Development Bank is providing up to $10 billion dollars for Covid-19 relief (Massdorp 2020).

- The New Development Bank has approved a $1 billion loan to both South Africa and India to combat the Covid-19 pandemic.

- The New Development Bank has approved a $7 billion loan to China to combat the Covid-19 pandemic.

- The New Development Bank approved a $1 billion loan to Brazil for Covid-19 pandemic-related assistance. This loan is New Development Bank's biggest loan approval to Brazil thus far. Loan approvals from New Development Bank to Brazil constitute 13% of the New Development Bank's portfolio (New Development Bank 2020a).

"The COVID-19 Emergency Program Loan to Brazil will contribute to the country's ongoing efforts to strengthen social safety nets and address immediate socio-economic impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak, particularly on the most vulnerable population in Brazil." - Mr. Marcos Troyjo, President of the New Development Bank. "It also represents an important milestone for the Government of Brazil and New Development Bank in the fight against COVID-19, in coordination with other multilateral development banks and development agencies."

New Development Bank and Russia:

In September 2020, the New Development Bank approved a $100 million loan to Russia for its transport strategy to increase transport connectivity throughout the country (Russia Briefing 2020). The Toll Roads Program is set to reduce the cost of transportation and easy access to distant cities in the country (New Development Bank 2020). The New Development Bank also approved a $100 million loan to Russia for its Eurasian Developmental Bank for the Water Supply and Sanitation Program, which modernizes water supply and sanitization systems (BRICS 2020). The programs are estimated to take four years to implement.

The plans to open the first New Development Bank in Russia were delayed to 2021 (BRICS 2020).

In March of 2022 and in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the AIIB (backed substantially by China and described in greater detail below) halted all businesses with Russia, and the NDB (created by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) announced it would put new transactions in Russia on hold. The future of Russia’s relationships with both banks is uncertain, but it is significant that China has significant stakes in the two banks (more than 30% shareholding in the AIIB and 19% in NDB).

U.S. Domestic Security/NAFTA

NAFTA vs. USMCA:

In September 2018, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) was confirmed to replace the 25-year-old North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The USMCA officially went into effect on July 1, 2020 (Chatzky et al. 2020). The USMCA shares many similarities with NAFTA, however, some key differences may require businesses and operations to adapt or evaluate their operations.

NAFTA included exemption from tariffs and quotas for eligible products among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. However, because the USMCA implemented new rules, customs administration, and room for interpretation, some businesses have had to reevaluate their products to meet qualifications and preferential tariff treatment. The new rules include:

- Changes in product-specific and process-specific rules of origin

- Increase in the de minimis content threshold for non-originating materials

- Changes to the regional value calculation are used to determine how much of a good's domestic materials and processing may be considered originating country status.

The origin status of a good is of major concern under the newly implemented USMCA (Assuncao et al. 2020). NAFTA Certificates of Origin are no longer in effect, businesses and manufacturers will have to meet USMCA Certificates of Origin to certify for eligibility. This has already affected the auto industry, as the USMCA requires 75% of each vehicle to originate in the member countries, up from 62.5% under NAFTA. The USMCA mandates that automakers manufacture 40% of their vehicles in facilities where workers earn at least $16/hour (Chatzky et al. 2020). The cost of manufacturing auto parts in Mexico will rise as worker wages rise. Although the purpose is to incentivize automakers to manufacture car parts in America, critics warn that as reliance on inexpensive parts sourced from abroad decreases, production costs will steeply increase. However, Ford, the US-based automaker, applauded the agreement stating that the USCMA will “support an integrated, globally competitive automotive business in North America” (Stuart 2018).

The USMCA eliminated the investor-state dispute settlement mechanism with Canada. In return, Canada will allow more access to its dairy market and several concessions in its favor, such as the Chapter 19 dispute panel which it relies on to protect itself from U.S. trade remedies (Chatzky et al. 2020).

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Without the United States

The U.S. watches from the sidelines as China furthers its trade and investment partnerships worldwide. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was signed in November of 2020. The participating countries, which include China, Japan, and Australia, account for about 30% of the global GDP. The pact is intended to reduce trade barriers between signees and facilitate business deals. The RCEP lowers and/or eliminates tariffs on various goods and services between the countries who take part in the RCEP. By making it easier for the RCEP signees to trade with one another, it makes it harder for U.S. companies to compete in Asia. The deal is symbolic of China’s power, and America’s waning influence, in the Asia-Pacific region. Japan, South Korea, and Australia are allies of the United States, however, they moved forward with the RCEP even in the absence of the U.S.

“The trade pact more closely ties the economic fortunes of the signatory countries to that of China and will over time pull these countries deeper into the economic and political orbit of China.”- Eswar Prasad (professor of economics and trade policy at Cornell University, former head of International Monetary Fund China Division).

The RCEP is “the first multilateral trade deal for China, the first bilateral tariff reduction arrangement between Japan and China, and the first time China, Japan, and South Korea have been in a single free-trade agreement.” (Gunia 2020). List of RCEP signatories (McCarthy 2020): Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was a part of the Obama Administration's plan to extend its influence and counter China's rise in the Asian market. The TPP included human rights, environmental rights, intellectual property and labor regulations that bolster U.S. competitiveness in the Asian market. As China's major trade partners signed up, the Obama Administration hoped that China would be forced to give in and join as well. However, President Trump withdrew from TPP on his first day in office in 2017, taking an isolationist approach.

With the U.S. out of the picture, the RCEP backed by China does not include labor or environmental standards (Gunia 2020). The U.S. Chamber of Commerce released a statement shortly after the signing of the RCEP in November 2020, stating that the United States "should however adopt a more forward-looking, strategic effort to maintain a solid U.S. economic presence in the region. Otherwise, we risk being on the outside looking in as one of the world's primary engines of growth hums along without us (U.S. Chamber 2020). China's already dominant presence in most Asian economies is set to grow under RCEP (Albert 2020).

“The U.S. now has even less leverage to pressure China into modifying its trading and economic practices to bring them more in line with U.S. standards on labor, the environment, intellectual property rights protection, and other issues related to free trade” - Eswar Prasad (professor of economics and trade policy at Cornell University, former head of International Monetary Fund China Division) (Gunia 2020).

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)

Launched by Beijing in 2014 and established in 2015, and widely understood to be a way for China to expand its influence, the AIIB is a multilateral development bank that aims to support building infrastructure in the Asia-Pacific region.

The bank currently has 74 members as well as 26 prospective members from around the world. It started operation when the agreement entered into force on 25 December 2015, after ten member states (including the U.K.) holding a total number of 50% of the initial subscriptions of the Authorized Capital Stock ratified the bank. While the AIIB has pledged to be "lean, clean, and green," it is plunged into a variety of mega fossil fuel and hydro projects from its founding. In addition, there are concerns about the minimum oversight and transparency of its practices.

Nevertheless, the AIIB has received the highest credit ratings from the three biggest rating agencies in the world and is seen as a potential rival to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. After all, since the end of WWII, the U.S. and Western Europe (along with Japan) controlled most of the business of loaning money to poor countries, loans which often came with strict economic, ethical and environmental behavior, while gaining significant political clout. China (and other superpowers) want a share of that political clout. And it is timing could not be better, since the Trump administration has repeatedly reduced the role of the United States in global financial institutions.

Recent Examples of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank Loans

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Middle East:

The AIIB’s funding of new projects and growing interest in the Middle East is alarming the United States and the Western World (Rakhmat 2020). In March of 2020, AIIB provided a $60 million loan to Oman which will allow the country to build its biggest solar power project to date, a greenfield solar power plant. Through this solar power plant, Oman will reduce its reliability on fossil fuels for electrical generation and increase its renewable power generation capacity (AIIB 2020a). Although the AIIB previously approved two major loans for construction projects in Oman, this loan marks the first renewable energy financing for AIIB in the Middle East. For the first time in its history, the AIIB will hold its annual meeting in the Middle East. The AIIB will converge for its annual meeting in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in October of 2021 (Rakhmat 2020). Some economists claim that these configurations will facilitate the heavy influence of Chinese political and economic interests in the Middle East (Fulton et al. 2019). Unlike the International Monetary Fund, the AIIB does not attach terms and conditions to loans and emphasizes transparency and simplicity. The “promise of no-strings-attached infrastructure financing” plays a major role in the Middle East’s support of the AIIB (AMEinfo 2017). The United States worries that AIIB's growing presence in the Middle East could result in Middle Eastern countries supporting and participating in Chinese economic and political interests, weakening the power of the United States in the region (Fulton et al. 2019).

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and India:

As of 2019, India has become the largest recipient of AIIB funding (BRICS 2020). In October of 2020, the AIIB approved a loan of $500 million for the construction of a rapid transit system. The high-speed rail will allow travelers to make the 82 Kilometer journey from Sarai Kale Khan in Delhi to Modipuram in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh in under an hour (AIIB 2020b). The approval of this loan came just three months after the AIIB approved a loan of $750 million to India for Covid-19 assistance (Krishnan 2020). As of late, tensions between India and China have been high as disputes continue along the Himalayan border region. The two countries have even blocked mobile apps from the other country due to privacy and security concerns. However, the AIIB maintains its stance as an apolitical institution and vows to only look at projects from economic and financial points of view, not a political view. The AIIB maintains that the rising tensions between the two countries will have no effect on its future decisions to approve loans for India (Zhou 2020).

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and Covid-19:

The AIIB created a Crisis Recovery Facility in response to the Covid-19 global pandemic. The Crisis Recovery Facility provides financial support to both public and private sector entities at risk of facing significant adverse impacts due to the Covid-19 Pandemic. The Crisis Recovery Facility plans to loan up to USC 13 billion over 18 months (April 2020 – Oct 2021) (AIIB 2022).

As the AIIB acquires several new borrowers through its Covid-19 relief, some economists question whether the distance between China and the AIIB is sizeable enough. However, there has been no proof of the Chinese government manipulation of loans thus far (Ayse et al. 2021).

As of December 2020, the AIIB provided Covid-19 relief to the following countries (AIIB 2020c):

- Pakistan: USD 500 million

- Bangladesh: USD 300 million

- Turkey: USD 100 million

- India: USD 750 million

- Maldives: USD 7.3 million

- Cook Islands: USD 20 million

- Georgia: USD 100 million

- Ecuador: USD 50 million

- Uzbekistan: USD 200 million

- Mongolia: USD 100 million

- Indonesia: USD 750 million

- Thailand: USD 500 million

- Philippines: USD 750 million

How to Succeed Cross-Culturally

In any global transaction, cross-cultural knowledge and understanding are essential. Learning the laws, political differences, differing governmental systems, and cultural differences represented by those involved in the transaction will significantly facilitate a smooth and successful transaction. Dominant societal culture influences the behavior of those within the culture, making culture a significant element in deal negotiation, whether they occur in the context of a merger, acquisition, partnership, joint venture, or other cross-cultural relationships. In other words, it is not sufficient to simply arrive with an appropriate gift or hold the door open for someone. Rather, culture, used in this context, is the broader norms and, as well as the sub-norms and sub-values, of the country, community, and company with which you are dealing. Each aspect is a significant component of successful international transactions and deserves substantial research and evaluation. Thus, cultural differences between countries, even those that may seem small, carry substantial weight in the global transactions space. They can be the difference between a successful venture and an utter failure.

The chaotic merger of Daimler-Benz and Chrysler serves as a great example.

In 1998 Daimler-Benz and Chrysler announced a merger of the two companies which, at the time, was one of the biggest cross-border industrial mergers. The amalgamation of the two companies initially produced global sales of over $150 billion. Daimler-Benz (a German company) and Chrysler (an American company), foresaw potential cultural differences and attempted to pre-emptively address these issues. Chrysler sent an American team to the Daimler-Benz headquarters in Sindelfingen, Germany to give presentations on differing communication styles between the two cultures. This, however, ultimately proved to be insufficient as diversity in communication styles led to early misunderstanding and conflict, and later structural and procedural differences, which then led to the demise of the original economic strength of the merger.

Just one of the many key cultural differences this case study demonstrates is the significance of seemingly insignificant communication styles.

In the American communication style, the usage of speech is factual but also opinionated and persuasive. Americans often use “hype.” They’re optimistic and present best-case scenarios. They have a “let’s get-on-with-it” approach, show up to business meetings with “Hollywood smiles,” and have an appreciation and usage of humor. A lot of their encounters, even the most serious business encounters, have an aura of casualness about them.

Conversely, in the German communication style, the primary purpose of speech is to give and receive information. They instinctively react adversely to usage of “hype.” As a general matter, they are somewhat cautious, somewhat pessimistic, and envisioning worst scenarios. They like to appreciate the full context before approaching important decisions, and rather than a Hollywood Smile, they have a more “serious look” in new business meetings. Overall, Germans tend to have a far greater appreciation of seriousness and clarity.

Due to these communication barriers and the structural and procedures issues that arose out of them, DaimlerChrysler’s share price fell from $108 in 1999 to $38 in 2000. While it has since recovered quite a bit, the lesson holds.

When considering the significance of cultural differences, we should include not just social norms, but also political, social, legal, linguistic, religious, and diplomatic considerations.

There are, primarily, two challenges to cross-cultural challenges to overcome when engaged in a cross-border/global deal:

First, Challenges Related to Interpersonal Relationships. In any deal or venue, even (perhaps especially) in an adversarial context, forging relationships is key. Relationships are key to earning respect from your colleagues and adversaries, finding creative solutions to difficult negotiation problems, and overcoming deal failures and obstacles.

Second, Challenges Related to Expectations. Sophisticated actors in the global marketplace understand that they must alter their expectations of results based on where and who they are negotiating/collaborating with. It is folly, for example, to assume the rest of the world moves at the same fast tempo as Americans do when it comes to closing a deal. Expecting the deal to close at the pace that your cultural standards set might, in fact, endanger the deal from coming to fruition.

To succeed, you should:

- Avoid creating a negative impression

- Endeavour to create a positive impression

- Manage client and supervisor expectation

- Remember that you are in their country

- Remember that the rules do apply to you

- Ensure your entourage understands this as well as you do

- Be the right person/Send the right person

- Do not criticize, even if locals do

The ease of interactions become far easier the more experience one gains with a particular culture. There are, however, many ways to prepare oneself even for a first-time encounter.

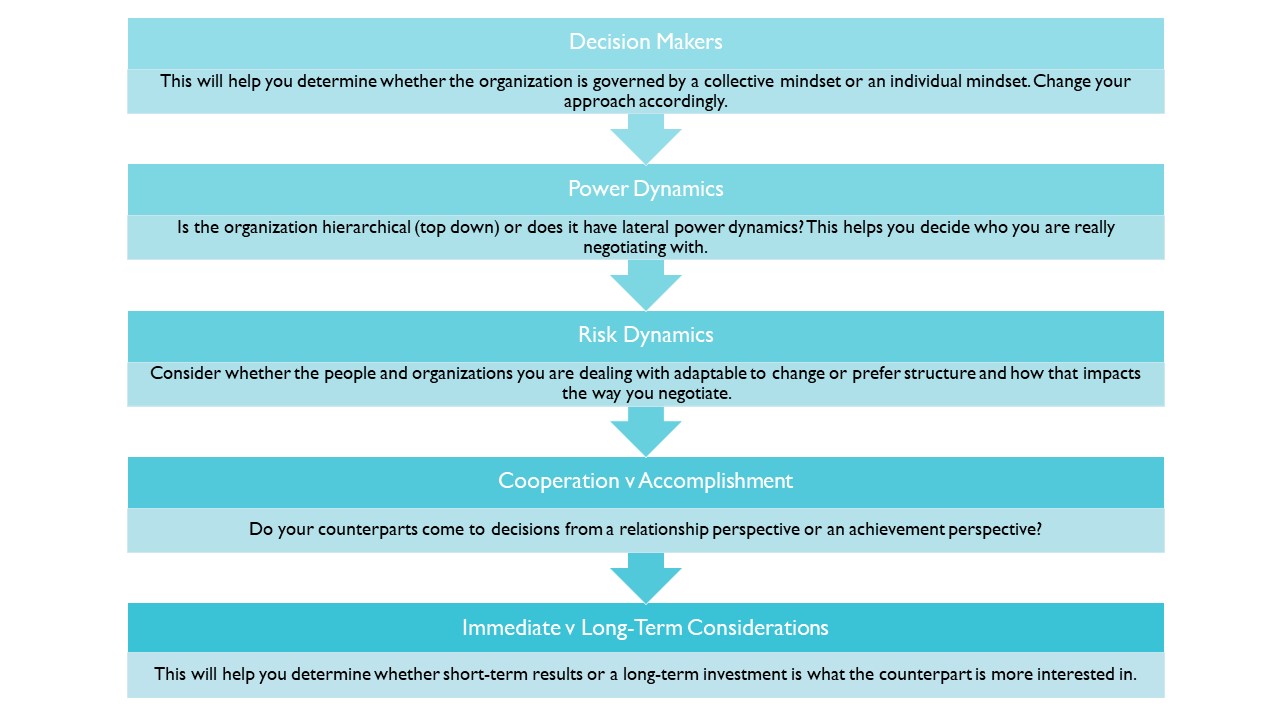

The below chart of questions and reflections is a helpful breakdown of the type of information negotiators seek in a cross-cultural context. Understanding these key decision-making influences within the cross-culture context will maximize the likelihood of transaction success, potential partnerships, and post-transaction integrations.

While the breakdowns above are presented as two opposing alternatives, the reality is that the pendulum will typically fall in some blend of the two extremes and can swing from side to side. Nevertheless, the contradictions help cross-border transactors navigate cultural pitfalls.

Practical Niceties Regardless of the Culture

- Arrive with food and appropriate gifts

- Consider your clothing careful. In most cultures, casual does not mean blue jeans

- Be mindful of how you present your business card and documents

- Note the appropriate timing of meetings. In some cultures, breakfast meetings are a non-starter. They might meet you for breakfast, but it is understood that it would be inappropriate to talk business until closer to 10 a.m.

- In nearly every culture, members of the culture like it when outsiders express interest and appreciation of their culture:

- Ask about food and praise it

- Attend the theater or a musical performance

- Appreciate the architecture

- Help the people around you understand you better. Avoid conjunctions, smile, do not speak too fast, and try to mimic the body language you observe around you. If they do not understand you, assume the fault is yours and reflect on what you can do to improve

- If you are making an attempt to speak the local language, it helps to let the other person know that. Unless your accent is very good, it is possible they will not understand you – do not be offended

- If you can do it without creating some type of risk, always follow up in writing and provide written summaries

- Do not judge competence or morality by English ability or education

- If faced with a moral cultural clash or conflict, carefully consider your response to the situation and perhaps consult with colleagues before responding

- And last but not least, be a nice person, care about other people, and trust your ethical core.

Case Study: IKEA

By Deepa Ganesh, Nadia Natt, Theresa Larosilliere, Varun Pradeep Kumar, and Stephanie Chai.

Bibliography

AIIB 2020a

“AIIB’s USD60-M Solar Investment in Oman Supports Diversified Energy Mix - News.” 2020. Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. https://www.aiib.org/en/news-events/news/2020/AIIBs-USD60-M-Solar-Investment-in-Oman-Supports-Diversified-Energy-Mix.html

AIIB 2022

“AIIB Looks to Launch USD5 Billion COVID-19 Crisis Recovery Facility.” 2022. AIIB. https://www.aiib.org/en/news-events/news/2020/AIIB-Looks-to-Launch-USD5-Billion-COVID-19-Crisis-Recovery-Facility.html

BRICS 2020

“India Biggest Borrower from China-Based Bank for Covid-19 Relief Fund.” 2020. BRICS. https://infobrics.org/post/31527/

Al Jazeera 2020

Al Jazeera. 2020. “‘Deliberate Depression’: World Bank’s Dire Warning on Lebanon.” Business and Economy News. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2020/12/1/deliberate-depression-world-banks-dire-warning-on-lebanon

Albert 2020

Albert, Eleanor. 2020. “China Leans into RCEP Conclusion as Win.” The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2020/11/china-leans-into-rcep-conclusion-as-win/

AMEinfo 2017

AMEinfo. 2017. “No globalization, China’s Silk Road and the Middle East.” https://www.ameinfo.com/industry/business/neoglobalization-chinas-silk-road-middle-east

AIIB 2020b

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. 2020. “India: Delhi-Meerut Regional Rapid Transit System”. Project Summary Information 3, Chart vertical line 2. AIIB. https://www.aiib.org/en/projects/details/2020/approved/India-Delhi-Meerut-Regional-Rapid-Transit-System.html

AIIB 2020c

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. 2020. “Our Projects”. AIIB. https://www.aiib.org/en/projects/list/year/2020/member/All/sector/All/project_type/All/financing_type/All/status/All

Assuncao et al. 2020

Assuncao, Robert A., and David A. Gonzalez. 2020. “US-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) Rules of Origin and the Impact on Domestic Manufacturers.” Lexology. Ansa Assuncao LLP. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=19b6e271-bc9b-4265-8b17-2335547873c0

BBC News 2010

BBC News. 2010. “Eurozone Approves Massive Greece Bail-Out.” BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/8656649.stm

Carassava 2004

Carassava, Anthee. 2004. “Greece Admits Faking Data to Join Europe.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/23/world/europe/greece-admits-faking-data-to-join-europe.html.

Chatzky et al. 2020

Chatzky, Andrew, McBride, James, and Sergie, Mohammed Aly. 2020. “NAFTA and the USMCA: Weighing the Impact of North American Trade.” 2020. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/naftas-economic-impact

Council on Foreign Relations 2022

Council on Foreign Relations. 2022. “Greece’s Debt Crisis Timeline.” Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed March 18. https://www.cfr.org/timeline/greeces-debt-crisis-timeline

Dullien 2012

Dullien, Sebastian. 2012. “Reinventing Europe: Explaining the Fiscal Compact.” ECFR. https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_reinventing_europe_explaining_the_fiscal_compact

European Council 2022

European Council. 2022. “How the Eurogroup Works.” 2022. Consilium. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/eurogroup/how-the-eurogroup-works/

Fulton et al. 2019

Fulton, Jonathan, Lons, Camile, Sun, Degang, and Al-Tamimi, Naser. 2019. “China’s Great Game in the Middle East.” ECFR. https://ecfr.eu/publication/china_great_game_middle_east/

Goodman 2020

Goodman, Peter S. 2020. “How the Wealthy World Has Failed Poor Countries during the Pandemic.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/01/business/coronavirus-imf-world-bank.html

Gunia 2020

Gunia, Amy. 2020. “Why the United States Could Be the Big Loser in the Huge RCEP Trade Deal Between China and 14 Other Countries”. Time. https://time.com/5912325/rcep-china-trade-deal-us/

IMF 2020

International Monetary Fund. 2020. “IMF Executive Board Approves Immediate Debt Relief for 25 Countries.” IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/13/pr20151-imf-executive-board-approves-immediate-debt-relief-for-25-countries

IMF 2021

International Monetary Fund. 2021. “Factsheet - The Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust.” 2021. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/16/49/Catastrophe-Containment-and-Relief-Trust

IMF 2022b

International Monetary Fund. 2022." Questions and Answers: The IMF’s Response to Covid-19." IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/imf-response-to-covid-19

IMF 2022

International Monetary Fund. 2022. “IMF Financing and Debt Service Relief.” IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/COVID-Lending-Tracker

Johnston 2021

Johnston, Matthew. 2021. “Understanding the Downfall of Greece’s Economy.” Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/070115/understanding-downfall-greeces-economy.asp

Ayse et al. 2021

Kaya, Ayse, Kilby, Christopher, Kay, Jonathan. 2021. “The AIIB’s Risky Pandemic Response.” Reconnecting Asia. https://reconasia.csis.org/aiibs-risky-pandemic-response/

Kottasová 2018b

Kottasová, Ivana. 2018. “Tanzania Loses $300 Million World Bank Loan Amid Crackdown Concerns.” CNN Business. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2018/11/13/africa/tanzania-world-bank-loan-intl/index.html

Kottasová 2018a

Kottasová, Ivana. 2018. “They Failed Mandatory Pregnancy Tests at School. Then They Were Expelled.” CNN. Cable News Network. https://www.cnn.com/2018/10/11/health/tanzania-pregnancy-test-asequals-intl/index.html

Kottasová 2020

Kottasová, Ivana. 2020. “World Bank Delays Vote on $500 Million Loan after Activist Letter on Ban on Pregnant Schoolgirls.” CNN. Cable News Network. https://www.cnn.com/2020/01/27/africa/tanzania-world-bank-loan-pregnant-girls-intl/index.html

Krishnan 2020

Krishnan, Ananth. 2020. “One-Third of Funding by AIIB Has Gone to India.” The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/business/Industry/one-third-of-funding-by-aiib-has-gone-to-india/article32699050.ece

Massdorp 2020

Leslie, Maasdorp. 2020. “Covid-19: How Multilateral Development Banks Can Lead through a Crisis.” World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/07/brics-new-development-bank-leads-member-states-through-the-covid-19-crisis/

McCarthy 2020

McCarthy, Niall. 2020. “15 Countries Have Signed the World’s Biggest Free Trade Deal Infographic.” Forbes Magazine. https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2020/11/16/15-countries-have-signed-the-worlds-biggest-free-trade-deal-infographic/?sh=50d789b4195f

McLeod 2020

McLeod, Sheri-Kae. 2020. “World Bank Provides Additional Financing of US$26 Million to Strengthen Flood Risk Management in Guyana.” Caribbean News. https://www.caribbeannationalweekly.com/caribbean-breaking-news-featured/world-bank-provides-additional-financing-of-us26-million-to-strengthen-flood-risk-management-in-guyana/

Milne 2009

Milne, Seamus. 2009. “Noam Chomsky: ‘Us Foreign Policy Is Straight out of the Mafia’.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/07/noam-chomsky-us-foreign-policy

New Development Bank 2020a

New Development Bank. 2020. “NDB Approves USD 1 Billion COVID-19 Emergency Program Loan to Brazil”. New Development Bank. https://www.ndb.int/press_release/ndb-approves-usd-1-billion-covid-19-emergency-program-loan-brazil

New Development Bank 2020

New Development Bank. 2020. “Projects.” New Development Bank. https://www.ndb.int/toll-roads-program-in-russia/

Ng’wanakilala 2020

Ng’wanakilala, Fumbuka. 2020. “World Bank Finally Approves $500 Million Tanzania School Project.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-01/world-bank-finally-approves-500-million-tanzania-school-project

Nyeko 2020

Nyeko, Oryem. 2020. “Tanzania Drops Threat of Prison over Publishing Independent Statistics.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/03/tanzania-drops-threat-prison-over-publishing-independent-statistics

OECD 2020

OECD. 2020. OECD Economic Surveys: Greece. https://www.oecd.org/economy/greece-economic-snapshot/

Oxfam International 2020

Oxfam International. 2020. “The IMF Must Immediately Stop Promoting Austerity around the World.” Medium. https://oxfam.medium.com/the-imf-must-immediately-stop-promoting-austerity-around-the-world-49a8d7ba7152

Rakhmat 2020

Rakhmat, Muhammad Zulfikar. 2020. “How the AIIB Grows China’s Interests in the Middle East.” The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2020/09/how-the-aiib-grows-chinas-interests-in-the-middle-east

Reuters 2019

Reuters. 2019. “Greece Concludes Early Repayment of IMF Loans.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-greece-economy-imf/greece-concludes-early-repayment-of-imf-loans-idUSKBN1XZ23V

Reuters 2020

Reuters. 2020. “IMF to Close Athens Office as Greece Recovers after Crisis: Greek PM.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-greece-economy-imf/imf-to-close-athens-office-as-greece-recovers-after-crisis-greek-pm-idUSKBN1Z62IY

Russia Briefing 2020

Russia Briefing. 2020. “BRICS Bank Finances Black Sea Trade, Toll Roads & Water Supply Projects in Russia.” 2020. Dezan Shira and Associates. https://www.russia-briefing.com/news/brics-bank-finances-black-sea-trade-toll-roads-water-supply-projects-in-russia.html/

Stokes 2020

Stokes, Bruce, and Sara Kehaulani Goo. 2020. “5 Facts about Greece and the EU.” Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/07/07/5-facts-about-greece-and-the-eu/

Stuart 2018

Stuart, Owen. 2018. “How Will the Shift from NAFTA to USMCA Affect the Auto Industry?”. Industry Week. https://www.industryweek.com/the-economy/article/22026500/how-will-the-shift-from-nafta-to-usmca-affect-the-auto-industry

Guardian 1999

The Guardian. 1999. “The People Always Pay.” Guardian News and Media. https://www.theguardian.com/world/1999/jan/21/debtrelief.development3

World Bank 2020

The World Bank. 2020. “EU, UN and WBG Launch an 18-Month Reform, Recovery and Reconstruction Framework in Response to Beirut Port Explosion.” World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/12/04/eu-un-and-wbg-launch-an-18-month-reform-recovery-and-reconstruction-framework-in-response-to-beirut-port-explosion

U.S. Chamber 2020

U.S. Chamber. 2020. “U.S. Chamber Statement on the Regional Comprehensive Partnership Agreement (RCEP).” Chamber of Commerce. https://www.uschamber.com/international/us-chamber-statement-the-regional-comprehensive-partnership-agreement-rcep

World Bank Group 2020a

World Bank Group. 2020. “The World Bank in Guyana.” The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/factsheet/2020/09/02/the-world-bank-in-guyana.

WHO 2022

World Health Organization. 2022. “Lebanon Explosion 2020.” 2022. WHO. https://www.who.int/emergencies/funding/appeals/lebanon-explosion-2020

Zettelmeyer, et al. 2021

Zettelmeyer, Jeromin, Álvaro Leandro, and David Xu. 2021. “The Greek Debt Crisis: No Easy Way Out.” PIIE. https://www.piie.com/microsites/greek-debt-crisis-no-easy-way-out

Zhou 2020

Zhou, Cissy. 2020. “AIIB Will Remain ‘Apolitical Institution’ despite China-India Tensions.” South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3095106/china-india-tensions-will-not-influence-aiib-newly-re