4 Watchdog Journalists

Jon Marshall

“The press’s obligation is to rock the boat.” – Ruben Salazar

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” – Ida B. Wells

“If I don’t have the moral courage to challenge authority … we don’t have journalism.” – James Foley

Media can play many different roles in our lives. It can entertain. It can connect people socially. It can promote products and services. It can be used by governments and other powerful institutions to shape people’s ideas. And journalists can use it to keep an eye on those same governments and institutions to warn us about corruption and dangerous uses of power.

This last function is known as watchdog journalism, which has played a crucial role in building democracy. In fact, the first attempt at a newspaper in North America performed this watchdog function back in 1690. Its publisher, Benjamin Harris, owned a coffee shop and bookstore in Boston when he decided to make some extra money by printing a three-page newspaper. (The fourth page was left blank, most likely so readers could add their own news and comments as it was passed from person to person). In this newspaper, Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestcik (yes, they spelled words differently back then), Harris alerted readers that the British colonial government had botched a military raid. The colonial leaders didn’t like this criticism, and they shut Publick Occurrences down after only one issue.

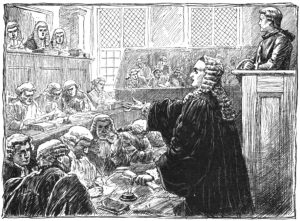

This kind of authoritarian, government control over news media was challenged in 1733 when John Peter Zenger dared to write in his New-York

Weekly Journal that the colonial governor, William Cosby, was allowing French ships to spy in New York City’s harbor. Cosby responded by having copies of the Weekly Journal burned, accusing Zenger of libel, and tossing him into jail.

Once again it looked like the government would crush the ability of the press – which in those days was just newspapers and pamphlets and soon magazines – to keep watch on government, but then something surprising happened. When Zenger’s case went to court, the jury agreed with his lawyer’s novel argument that something couldn’t be libelous if it was true. And they decided what Zenger published was indeed true. Zenger was released from jail, the Weekly Journal kept publishing, and an important precedent was set that journalists had the right to speak – and write – truth to power.

When the Unites States became an independent nation, its founders thought this watchdog role of the press was vital to liberty and enshrined it in the First Amendment to the Constitution. But once they were in charge, the country’s leaders weren’t always pleased with the free press’s aggressiveness. John Adams, the second president, became so frustrated with criticism of his government that in 1798 he signed into law the Sedition Act. The draconian law made it illegal to “write, print, utter, or publish … any false, scandalous and malicious writing … against the government of the United States.” Under the Sedition Act and similar local laws, more than 100 newspaper editors and other government critics were thrown in jail. Several opposition newspapers were forced to close. But the Sedition Act proved wildly unpopular and was one reason Adams lost the election of 1800. The next president, Thomas Jefferson, allowed the law to lapse.

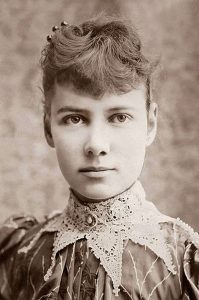

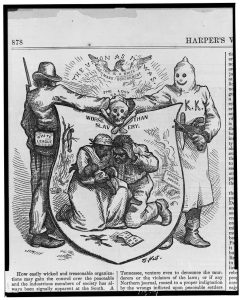

The power of the watchdog press isn’t confined to words. In the 1870s, Thomas Nast drew a series of cartoons for Harper’s Weekly magazine depicting the vast corruption of New York City’s Tammany Hall government and its leader, William “Boss” Tweed. Nast’s popular cartoons and stories by the New York Times pressured prosecutors to finally arrest Tweed, who was convicted of stealing the equivalent in today’s money of millions of dollars from taxpayers. Toward the end of the 1800s, journalists became increasingly daring in their investigations of society’s wrongs. Ida B. Wells, editor of the Memphis Free Speech, risked her life to write about how white leaders used lynchings of innocent people to terrorize the Black community. Elizabeth Cochrane, who used the pen name Nellie Bly, went undercover to expose the terrible abuse at an insane asylum, prompting New York’s government to improve its conditions. She also investigated prisons, hospitals, and factories, leading to more reforms.

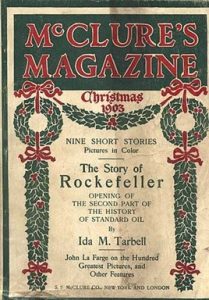

Watchdog journalism reached a peak in the early 1900s with a group of journalists known as muckrakers. Lincoln Steffens traveled to cities around the country to expose the depths of their corruption and the connections between local businesses and crooked politicians. Samuel Hopkins Adams revealed that many substances sold as medicines didn’t work and were often dangerous, leading Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act. And a series of articles by Ida Tarbell proved that one of the nation’s most powerful companies, Standard Oil, used threats, bribes, and other illegal tactics to crush competitors, raise prices, and lower wages. Tarbell’s articles in McClure’s magazine led to a Supreme Court ruling that Standard Oil illegally restrained trade, forcing the company to dissolve.

Watchdog reporting again showed its ability to sniff out government corruption when Paul Y. Anderson of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch began investigating President Warren Harding’s administration. Anderson discovered in 1922 that some of Harding’s closest aides had accepted bribes from companies in return for selling Navy oil reserves to them at a steep discount. Stories by Andersonand other reporters prompted congressional hearings that led to the conviction of Interior Secretary Albert Fall.

When U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy began falsely accusing people of being communists in the early 1950s, a few brave reporters were willing to expose McCarthy’s lies. Ethel Payne of the Chicago Defender, for example, detailed how McCarthy had wrongly accused a Pentagon communications clerk of being a communist agent. In 1954 Edward R. Murrow, perhaps America’s most famous journalist at the time, devoted an entire episode of his CBS TV show “See It Now” to documenting McCarthy’s bullying and misleading statements. Murrow’s watchdog reporting contributed to McCarthy being censured by the Senate a few months later.

In the 1960s, Army generals and President Lyndon Johnson insisted that the United States and its allies were winning the Vietnam War. However, reporters such as David Halberstam of The New York Times and Morley Safer of CBS went on patrol with the troops and let Americans know that Johnson and the generals weren’t telling the truth and that U.S. forces were stuck in a stalemate. In 1971 the Times began publishing a secret Defense Department study, known as the Pentagon Papers, documenting that the government had been lying to the public about Vietnam for two decades. President Richard Nixon’s administration got a court to order to stop the Times from publishing the Pentagon Papers, but then The Washington Post started publishing them. When the administration got a court order to stop the Post, 19 other newspapers started publishing the Pentagon Papers. The Supreme Court eventually ruled that the government couldn’t stop publication of the Pentagon Papers, a major victory for the watchdog press.

A year later, the watchdog press gained its greatest attention after five men were caught breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C. Reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward of The Washington Post, Seymour Hersh of The New York Times, Sandy Smith of Time magazine, and Jack Nelson and Ronald Ostrow of the Los Angeles Times persistently investigated this Watergate scandal. Bernstein and Woodward, for example, found that President Nixon’s campaign had paid the burglars, destroyed evidence, and operated a secret campaign fund to spy on Democrats. As the journalists revealed the criminal behavior, the FBI, Congress and special prosecutors conducted their own investigations. It became clear that Nixon was deeply involved in an illegal effort to cover up the Watergate crimes. In the summer of 1974, the House Judiciary Committee passed three articles of impeachment against him. He resigned before the Senate could convict him.

Since Watergate, the news media has continued to keep a close eye on U.S. presidents. In 1986, the Lebanese magazine Ash-Shiraa revealed that President Ronald Reagan’s administration had secretly and illegally sent weapons to Iran in return for the release of seven American hostages. The New York Times and other news outlets investigated President Bill Clinton’s scandals, including involvement in a shady land deal known as Whitewater. During George W. Bush’s administration, Dana Priest of The Washington Post uncovered the existence of secret CIA prisons around the world that used harsh interrogation methods. The Times detailed how President Donald Trump only paid $750 in taxes in 2016 and 2017 despite saying he was a billionaire.

Through the years, watchdog journalism has continued to not just keep an eye on governments, but also powerful people and institutions in other realms. For instance, The Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” investigative team uncovered the Archdiocese of Boston’s protection of priests who had sexually abused children. Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey of The New York Times and Ronan Farrow of The New Yorker helped to launch the #MeToo movement when they revealed in 2017 that Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein had harassed and sexually abused dozens of women. A Washington Post investigation revealed in 2024 that more than 1,000 Native American children had been sexually abused in Catholic-run boarding schools.

Watchdog reporting has grown stronger as new technology allows reporters to collaborate on extensive investigations of global problems. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, for example, brought together 300 journalists on six continents to examine 11.5 million documents for the Panama Papers project. They found that 140 leaders around the world – including the king of Saudi Arabia, associates of Russian leader Vladimir Putin, and the family of China’s president – were using secret tax havens to siphon money out of their countries. As a result of the 2016 investigation, Iceland’s prime minister resigned, and Pakistan’s former prime minister was indicted.

INSERT VIDEO OF BOSTON GLOBE SPOTLIGHT INTERVIEW HERE

Digital technology also allows everyday citizens to act as watchdogs. When 17-year-old Darnella Frazier witnessed a Minneapolis police officer murdering George Floyd in 2020 by pressing a knee into his neck, she courageously recorded a video of the killing and shared it with the world. Her video helped to convict the police officer and sparked anti-racism protests around the world. Frazier showed us that it’s important for all of us to keep an eye on the powerful.

Along with its successes, the press has too often failed to fully and accurately report on some of the most important events in history. For example, many of the largest publications barely covered the Holocaust while it was occurring during World War II. Although the tiny Jewish Foreword newspaper reported in 1942 that 1 million Jews were being massacred or starved by Hitler’s Nazis, The New York Times and Time, Life, and Newsweek magazines made only occasional mentions of the Holocaust and buried them deeply within their publications. Other important stories also received scant attention from the mainstream press: the starvation of millions in the Soviet Union, the great migration of Black people from the South to the North to escape racial terror, the widespread violence and discrimination faced by LGBTQ+ people, and many others.

Why did these failures happen? For generations, most newsrooms consisted primarily of straight white men from a narrow range of backgrounds who did not have much understanding of communities other than their own. If the watchdog press is going to truly keep a close eye on those with positions of power and understand the issues that directly affect people, journalism must more thoroughly reflect all of society’s glorious diversity.

Key Takeaways

- Strong watchdog journalism is essential to a healthy democracy.

- Corrupt leaders and powerful institutions often try to block watchdog journalism so they can maintain power.

- Many investigative journalists have displayed tremendous courage through the years to expose wrongdoing that harms people.

- Advances in technology allow watchdog journalists to report and tell stories in new and powerful ways.

Watchdog Timeline

1690: Benjamin Harris launches first newspaper in America

Boston printer Benjamin Harris publishes the first attempt at a newspaper in North America, named Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick. Colonial authorities close it down after its first (and only) issue, which included a report on a recently botched military raid.

1733: John Peter Zenger is tried for libel in New York

Printer and journalist John Peter Zenger is accused of libel for his reporting in the New-York Weekly Journal, where he accused colonial governor William Cosby of allowing French ships to spy in New York City’s harbor. The jury ultimately acquits Zenger, finding that something can’t be libelous if it’s true and setting an important precedent that journalists have the right to speak – and write – truth to power.

1791: The First Amendment becomes part of the Constitution

Only three years after ratifying the Constitution, the United States ratifies the Bill of Rights, which adds 10 amendments designed to protect individual rights and liberties. The First Amendment specifically protects freedom of the press along with freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the right to peaceably assemble and the right to petition the government.

1798: President John Adams signs the Sedition Act

President Adams becomes so frustrated with criticism of his government that he outlaws writing or publishing “any false, scandalous and malicious writing… against the government of the United States” by signing the Sedition Act. Over 100 newspaper editors and other government critics were jailed and several opposition newspapers were forced to close before the wildly unpopular law was allowed to lapse by Adams’ successor, President Thomas Jefferson.

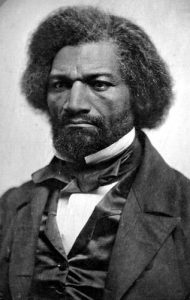

1820s-1860s: Abolitionist newspapers advocate for the end of slavery

Beginning in the 1820s and gaining momentum in the 1830s, the abolitionist press exposes slavery’s brutality and denounces government leaders who allow it to continue. Publications such as Frederick Douglass’ North Star and William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator are feared and outlawed by Southern leaders. The abolitionists later influence President Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and support the 13th Amendment, which abolished involuntary servitude except as a form of criminal punishment.

1892-1895: Ida B. Wells exposes the horrors of lynching

After the end of Reconstruction in 1877 comes the Jim Crow era, and former Confederate states reassert racial oppression by passing “Black Codes” and allowing lynchings and other acts of racial terror. As editor of the Memphis Free Speech, Ida B. Wells risks her life to report on and expose these attacks to the public, and she ultimately publishes this work in pamphlets titled Southern Horrors and The Red Record.

Early 1900s: Investigations by muckrakers lead to important reforms

Watchdog journalism reaches an early peak during the Progressive Era as crusading journalists (or “muckrakers”) expose corruption, dangerous working conditions and destitution nationwide, often in serialized works published in McClure’s and Collier’s magazines. These works led to significant reforms, such as the breakup of Standard Oil after Ida Tarbell exposes their monopolistic and illegal business practices, and the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act after Samuel Hopkins Adams reports on patent medicines’ danger to public health.

1922: Reporters expose the Teapot Dome scandal

Paul Y. Anderson of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch discovers that some of President Warren Harding’s closest aides had accepted corporate bribes in return for selling Navy oil reserves at a steep discount, kicking off the Teapot Dome scandal. He and other reporters publish stories which lead to Congressional hearings, eventually resulting in the conviction of Interior Secretary Albert Fall in 1929 for bribery and conspiracy.

Early 1950s: Journalists challenge Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunts

During the early Cold War, a few prominent journalists expose lies and fearmongering from U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who falsely accused numerous government officials of being Communist agents and sympathizers. Ethel Payne of the Chicago Defender details how McCarthy wrongly accused a Pentagon communications clerk of being a communist agent, and Edward R. Murrow dedicates an entire episode of his CBS show “See It Now” to documenting McCarthy’s bullying and misleading statements.

Late 1960s – Early 1970s: Vietnam War reporting and the Pentagon Papers case

As the Vietnam War drags on in the late 60s, reporters such as The New York Times’ David Halberstam and CBS’s Morley Safer contradict positive reports from Army generals and President Lyndon B. Johnson, going on patrol with American soldiers and showing that the war had become a stalemate. This reporting peaks in 1971 when the Times publishes the Pentagon Papers, a series of stories based on a leaked Defense Department report that reveal the military and several presidents had repeatedly lied about the scope and objectives of the war.

1972-1974: Reporting on Watergate scandal contributes to President Nixon’s resignation

After a group of men are caught breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters in June 1972, journalists across the country begin investigating their connection to President Richard Nixon. Two of these journalists, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post, reveal that Nixon’s campaign had paid the burglars, operated a secret campaign fund to spy on Democrats and hired people to sabotage their campaigns. This reporting helps prompt Congress to conduct its own investigations, and special prosecutors are appointed. Nixon ultimately resigns in 1974 before the House of Representatives can hold a full impeachment vote against him.

2002: Boston Globe’s Spotlight Team exposes widespread abuse and coverup in the Catholic Church

In January 2002, the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” investigative team publishes a series of stories revealing that the Archdiocese of Boston had protected dozens of priests from accusations of child sexual abuse, shuffling the priests between different churches and covering up allegations as they were made. The reporting leads to the prosecution of five priests and the resignation of American Cardinal Bernard Francis Law, and spurs reporting on similar coverups in other dioceses around the world.

2017: Reporting reveals Harvey Weinstein’s sexual abuse and helps launch #MeToo movement

New York Times journalists Megan Twohey and Jodi Kantor report in October 2017 that Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein had sexually harassed and paid settlements to at least eight of his female employees over the course of three decades. Follow-up reporting and public statements reveal over 100 accusations of harassment or assault and 18 accusations of rape against Weinstein, who is later convicted of numerous crimes in both New York and California. The reporting also helps spur #MeToo, a social media movement against sexual abuse in which people publicize their experiences of abuse or harassment.

2020: Darnella Frazier’s video of George Floyd’s murder goes viral

The police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis is recorded by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier, who posts it online. The video goes viral overnight, and the public’s outrage sparks mass protests and uprisings in cities across the United States and the world. The video is later used to convict one officer for murder and three other officers for violating Floyd’s civil rights.