11. Diacritics and conventions from Arabic and Persian

This chapter introduces several important orthographic conventions and grammatical functions that have been adopted into Urdu from Arabic and Persian.

Dagger alif

A dagger alif (also called khaṛā zabar ‘standing zabar’) is a diacritic that indicates an ā sound. It is written as a small vertical line above the consonant that it follows. It appears in a limited number of words whose spelling is borrowed from Arabic. Many of these words have religious connotations. It derives from an early period when even long vowels were not always consistently written in Arabic. Writing this diacritic is optional, and it is sometimes omitted:

رحمٰن

Rahmān ‘the Merciful’

الٰہ آباد

Ilāhābād ‘Allahabad’

لہٰذا

lihāzā ‘thus, for this reason’

Alif maqsūra

The alif maqsūra is another idiosyncratic orthographic feature adopted from Arabic. It is a long ā that is written as a chhoṭī ye. It may optionally be marked with a dagger alif. Bear in mind that, because writing the dagger alif is optional, the chhoṭī ye may thus be read as an ā even when it is not marked as such. Luckily, alif maqsūra only appears in a handful of cases, many of them names:

مصطفیٰ

Mustafā ‘Mustafa’

عیسیٰ

Īsā ‘Jesus’

موسیٰ

Mūsā ‘Moses’

لیلیٰ

Lailā ‘Laila’

دعویٰ

dāwā ‘claim’

Tanvīn

Another orthographic convention from Arabic that appears in Urdu is called the tanvīn. In Urdu, it almost always appears as two stacked zabar diacritics over an alif at the end of a word. It is pronounced as -an and creates an adverb:

تقریباً

taqrīban ‘approximately’

اولاً

avvalan ‘initially’

فوراً

fauran ‘immediately’

اتفاقاً

ittifāqan ‘by chance’

مثلاً

maslan ‘for example’

Izāfat

In Urdu, one way of adding qualifiers to nouns is to use a construction borrowed from Persian called the izāfat. The izāfat links two words, typically relating an adjective to a noun or showing possession. It is rarely used spontaneously in everyday speech, but it appears in a wide range of set phrases. It is used much more extensively in formal writing and poetry.

The izāfat is pronounced as a short e that appears between the linked words. Izāfat follows three patterns. It may be (noun X)-e (noun Y), meaning “X of Y,” as in shan-e Panjāb ‘the glory of Punjab.’ It can also appear as (noun X)-e (adjective Y), meaning “X with quality Y,” as in Muġhal-e Āzam ‘the greatest Mughal.’ Finally, it may appear as (adjective X)-e (noun Y), as in nā-qābil-e bardāsht ‘unbearable’ or, literally, ‘not capable of endurance.’

When writing an izāfat, the standard rule is to add a zer diacritic to the first word in the compound:

کتابِ مقدس

kitāb-e muqaddas ‘the Holy Book’ (the Bible)

جانِ من

jān-e man ‘my life’ (i.e., my love)

دردِ ڈسکو

dard-e ḍisko ‘pain of the disco’ (a comic phrase from the film Om Shanti Om)

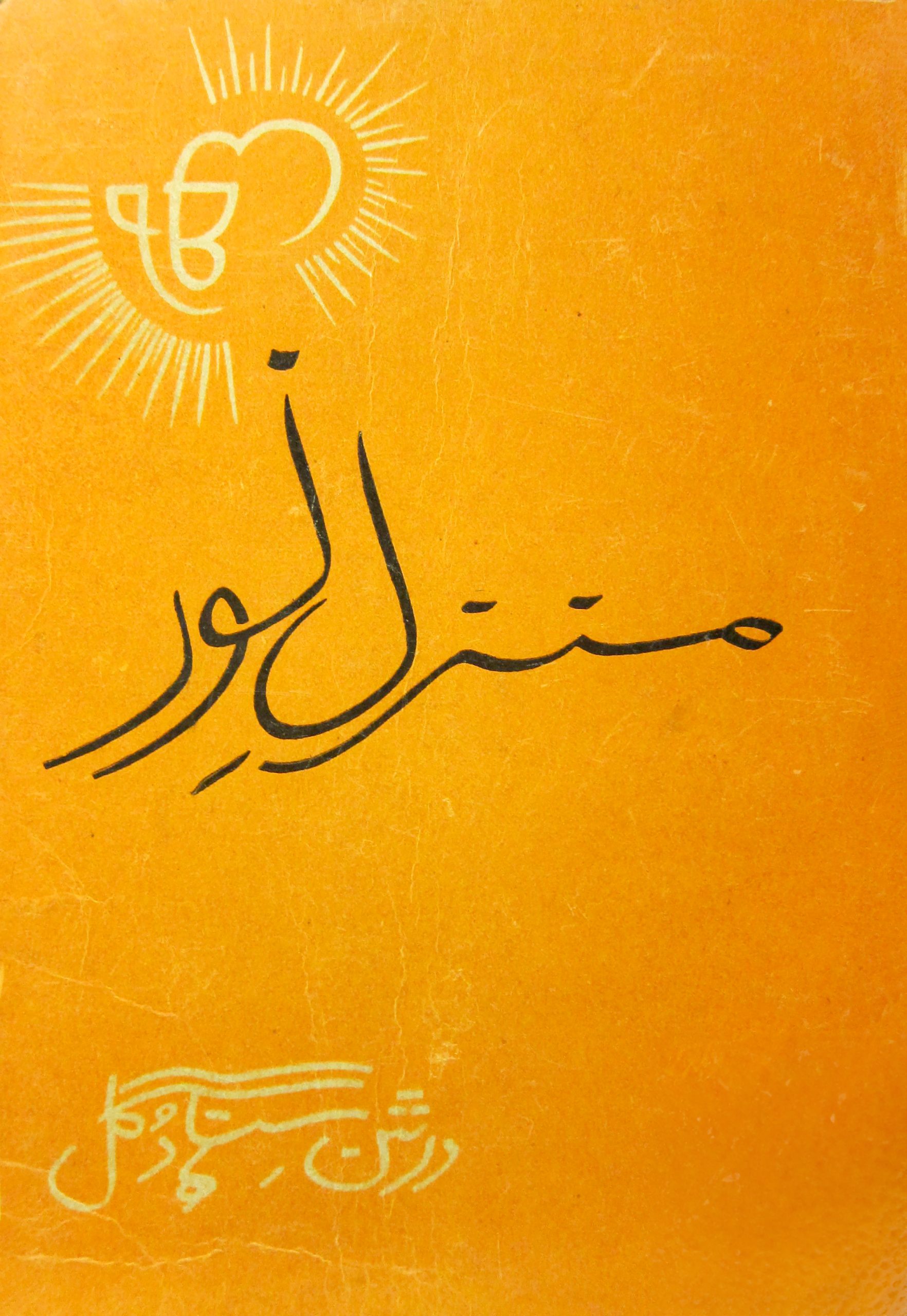

An example is the title of Manzil-e Nūr, by Darshan Singh Duggal (note too how the slashes of the gāf connect ‘Singh’ and ‘Duggal’):

Darshan Singh Duggal, Manzil-e Nūr (The Abode of Light). Image source: Misha Maltsev.

Darshan Singh Duggal, Manzil-e Nūr (The Abode of Light). Image source: Misha Maltsev.As you know, writing diacritics like zer is optional in Urdu. Thus, the izafat itself is sometimes not written, but must be inserted mentally by the reader. Learning to do so intuitively requires practice, but is not inherently difficult.

When the word receiving the izāfat ends in a vowel, indicating the izāfat becomes mandatory. If the word bearing the izāfat suffix ends in an alif or a wāw, then you should add hamza and baṛī ye:

زبانِ اردوئے معلیٰ

zabān-e urdū-e mu’allā ‘the language of the Exalted Camp (i.e. Urdu)’

When the word ends in a chhoṭī ye or a chhoṭī he that functions as a vowel, a hamza is usually written above the vowel (for chhoṭī he) or either above or beside it (for chhoṭī ye) to indicate the presence of an izāfat:

بیماریء دل

bīmārī-e dil ‘pain of the heart’

شوخئ تحریر

shoḳhī-e těhrīr ‘mischievousness of writing’

سفینۀ غمِ دل

safīna-e ġham-e dil ‘a vessel of the sorrows of the heart’

Note that when a word ends with a chhoṭī he functioning as a consonant, the izafat will not be indicated with a hamza but instead with an optional zer diacritic. Thus:

نگاہِ کرم

nigāh-e karam ‘a kind gaze’

ماہِ نو

māh-e nau ‘new moon’

But:

محکمۀ جنگلات

mahěkma-e jangalāt ‘Department of Forests’

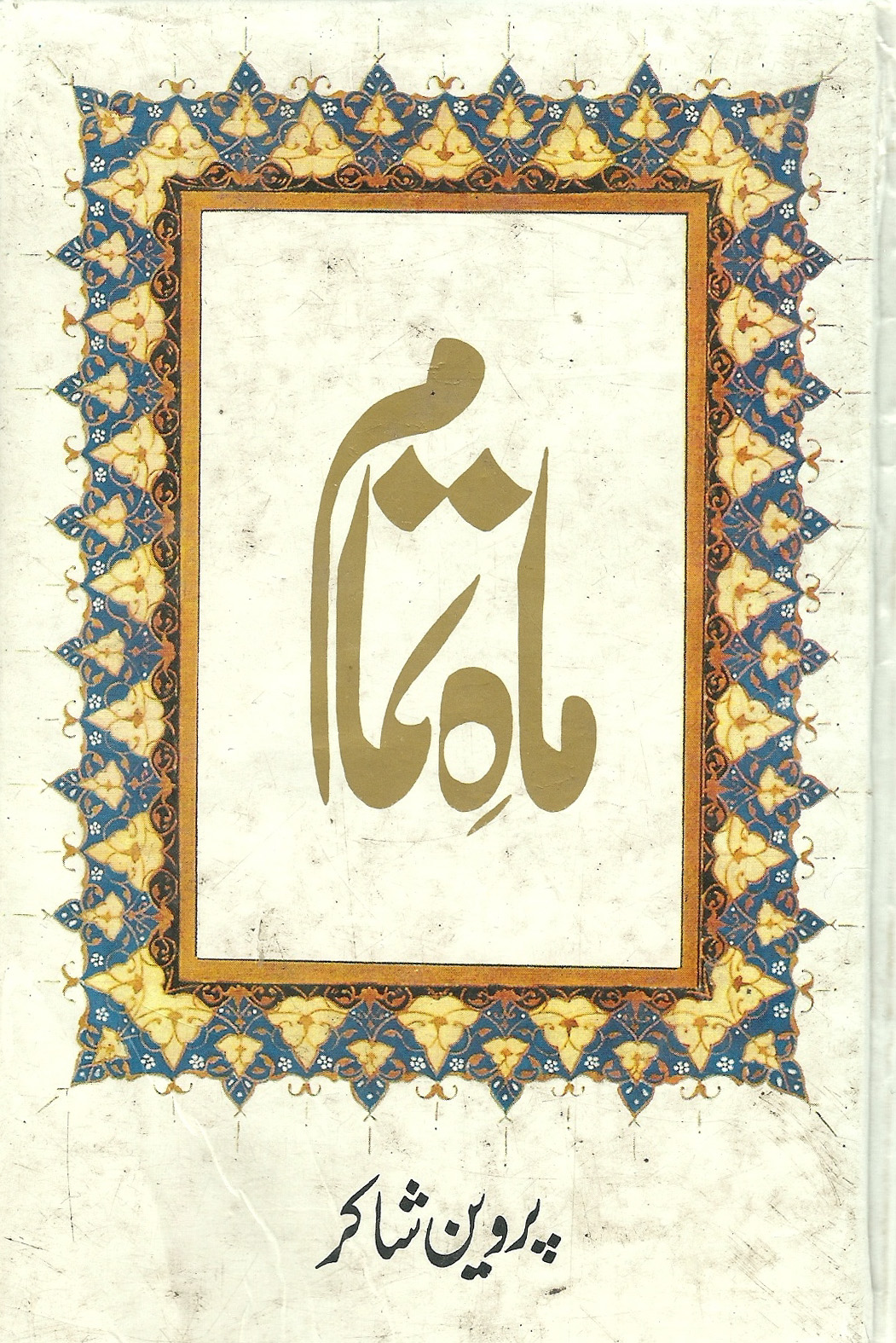

See, for example, this poetry collection:

Parvīn Shākir, Māh-e Tamām (The Full Moon).

The prefix al-

In Arabic, the prefix al- is used to mean “the,” “of,” and to link a definite noun and its attributes. It is widely used, often in set words and phrases, and its pronunciation frequently diverges from its spelling.

In some cases, the al- prefix has become practically part of a word:

الوداع

al-vidā ‘goodbye’

ﷲ

Al-lāh ‘Allah, God’

الجبرا

al-jabrā ‘algebra’

Less commonly, al- is also sometimes used creatively to give a particular word or phrase an Arabic flavor:

المشہور

al-mashhūr ‘the famous’

There are special rules for pronouncing the alif in the prefix al-, all of which derive from Arabic. When al- appears as the first element in a compound phrase, the alif is read as a short a, as in the words above. In any other position in an Arabic compound, the alif’s value is influenced by the vowel at the end of the word preceding it:[1]

کریم عبد الجبار

Karīm Abd ul-Jabbār ‘Karim Abdul-Jabbar’

رسم الخط

rasm ul-ḳhat ‘script (manner of writing)’

بالکل

bilkul (bi + al + kul) ‘completely (in the totality)’

فی الفور

filfaur (fī + al + faur) ‘immediately (in haste)’

فی الحال

filhāl (fī + al + hāl) ‘at present, for the time being (in the present)’

انشاء ﷲ

inshāllāh (inshā + Allāh) ‘God willing’

There are also special rules for pronouncing the lām in the prefix al-. In certain cases, the lām loses its quality as an l sound and instead doubles the following consonant. Whether or not this happens depends on where that following consonant is articulated by the tongue. The letters that are doubled after an al- represent the alveolar and dental sounds and are called shamsī or ‘sun’ letters (because shīn is one such letter):

|

Sound |

Letters |

|

t |

ت ط |

|

d |

د |

|

r |

ر |

|

s |

ث س ص |

|

sh |

ش |

|

z |

ز ذ ض ظ |

|

l |

ل |

|

n |

ن |

Shamsi letters that are doubled after an al- are sometimes marked with an optional tashdīd.

Here are some phrases featuring shamsī letters:

شمس الدّین

Shams ud-Dīn (shams + al + dīn) ‘Shamsuddin’

السّلامُ علیکم

as-salāmu alaikum (al + salāmu + alaikum) ‘peace be upon you’

بالترتیب

bittartīb (bi + al + tartīb) ‘in order’

All the other letters are not doubled. These are called qamarī or ‘moon’ letters.

Review

Izāfat and the prefix al- provide several ways to form compounds. The pronunciation of al- can vary depending on context.

In this chapter, we introduced these diacritics:

|

Diacritic |

Name |

Sound |

|

ٰ |

dagger alif / khaṛā zabar अलिफ़-ख़ंजरिया / खड़ा ज़बर |

ā आ |

|

یٰ |

alif-maqsūra अलिफ़-मक़्सूरा |

ā आ |

|

اً |

tanvīn तन्वीन |

an अन |

Exercises

- The rules governing these sound changes are somewhat complex. For a clear explanation of them, see pp. 78–79 of Mohammed Zakir’s Lessons in Urdū Script or pp. 138–141 of Gregory Maxwell Bruce’s Urdu Vocabulary. ↵