3. Te, mīm, jīm, che, and more diacritics

Te

Te makes a dental t or त sound. It follows the same pattern as be and pe; that is, it belongs to the be series. It is written with two dots side by side, above the main line:

|

ـت |

ـتـ |

تـ |

ت |

te ते |

|

|

t |

|||

Here are some words with te:

تِل

til ‘sesame’

بات

bāt ‘thing’

بُت

but ‘idol’

To save time in handwriting, sometimes a pair of dots (either by itself or as part of a three-dot group) can be replaced by a squiggle or a horizontal line, and a three-dot group can also be replaced by a circle or semicircle:

تاپ

tāp ‘heat’

Mīm

|

ـٮم |

ـٮمـ |

مـ |

م |

mīm मीम |

|

m |

||||

Mīm looks a bit different in calligraphy as opposed to handwriting. Because ordinary pens draw lines with more or less constant thickness, the head of a handwritten mīm is typically drawn as a counterclockwise loop. The tail of the independent or final mīm drops below the baseline.

Below are some words we can write using mīm:

کم

kam ‘less, little’

تُم

tum ‘you’

ململ

malmal ‘muslin cloth’

kumkum ‘saffron’

تمام

tamām ‘all’

Urdu letters sometimes change their shapes somewhat depending on the surrounding letters. In these words, you can see that a calligraphic mīm can sometimes be a little hard to spot in the initial or medial form. You can recognize it, though, because it’s the only letter that appears as a thickened bump hanging below the main line.

You might also notice that the initial te in tum and tamām looks a little different from usual: the be-series tooth has been smoothed out so that the pen immediately goes downward to form the mīm. We will occasionally point out these variations when they’re important for reading; for a more comprehensive view of them, consult the chart in Appendix C.

Jīm

The letter jīm sounds like j or ज:

|

ـٮج |

ـٮجـ |

جـ |

ج |

jīm जीम |

|

j |

||||

In jīm, the verticality of Urdu script is especially noticeable. In the final form, for instance, the pen enters the head from above, and the bowl curves below the baseline. Make sure the back corner of the head is pointed rather than rounded.

Insight

Instead of being hooked, the head of a letter in the jīm series can also be flat:

The difference is purely aesthetic and does not change how you read the letter.

Let’s look at some words with jīm:

jaj ‘judge’

āj ‘today’

جب

jab ‘when’

بجتا

bajtā ‘plays’

Sometimes the head of the jīm touches the line below it (but you should avoid this in your own handwriting until you are an expert):

کاجل

kājal ‘kohl, eyeshadow’

جام

jām ‘traffic jam’

Che

Another letter in the jīm series is che. It sounds like ch or च:

|

ـٮچ |

ـٮچـ |

چـ |

چ |

che चे |

|

ch |

||||

Che is written just like jīm, but with three dots below the head instead of one:

چال

chāl ‘trick’

chachā ‘uncle’

lālach ‘greed’

Practice

This picture contains three ches. Can you click on them?

Chachā Chhakkan, by Imtiaz Ali Taj. Image credit: Atlantis Publications.

More diacritics

In addition to zer, zabar, and pesh, there are a few other optional diacritics that we can use to clarify pronunciation. When a consonant is doubled—that is, pronounced longer than usual—we can mark it with a tashdīd, which looks a bit like a small w above the consonant:

کچّا

kachchā ‘raw’

اَبّا

abbā ‘father’

A tashdīd can be combined with a vowel diacritic. In this case, a diacritic that appears above a letter (like pesh or zabar) will be stacked above the tashdīd:

چمَّچ

chammach ‘spoon’

Note that the tashdīd works differently than double consonants in the Hindi and Roman scripts. Chammach, for instance, is written चम्मच in Hindi, with a half म् joined to a full म. In Urdu, by contrast, the consonant is only written once.

Sometimes, we want to specify that a consonant is not followed by any vowel at all (as with the halant ् that marks a half consonant in Hindi script). In Urdu we can use a sukūn (also called jazm) for this purpose. This symbol can take three different forms, all written above the consonant: a small circle, a circumflex (or caret), or something like an apostrophe:

ﹾ ْ ۡ

In the latter case, be careful not to confuse the sukūn with a pesh. You can tell them apart because only the pesh has a loop. Here are a couple of examples:

پتْلا

patlā ‘thin’

ب٘لاگ

blāg ‘blog’

Insight

The early Arabic script did not use either diacritics or dots, as in this image of a ninth-century Quran below:

After the Quran was written down, the use of dots and diacritics was standardized. Urdu has inherited the diacritic marks that were developed then.

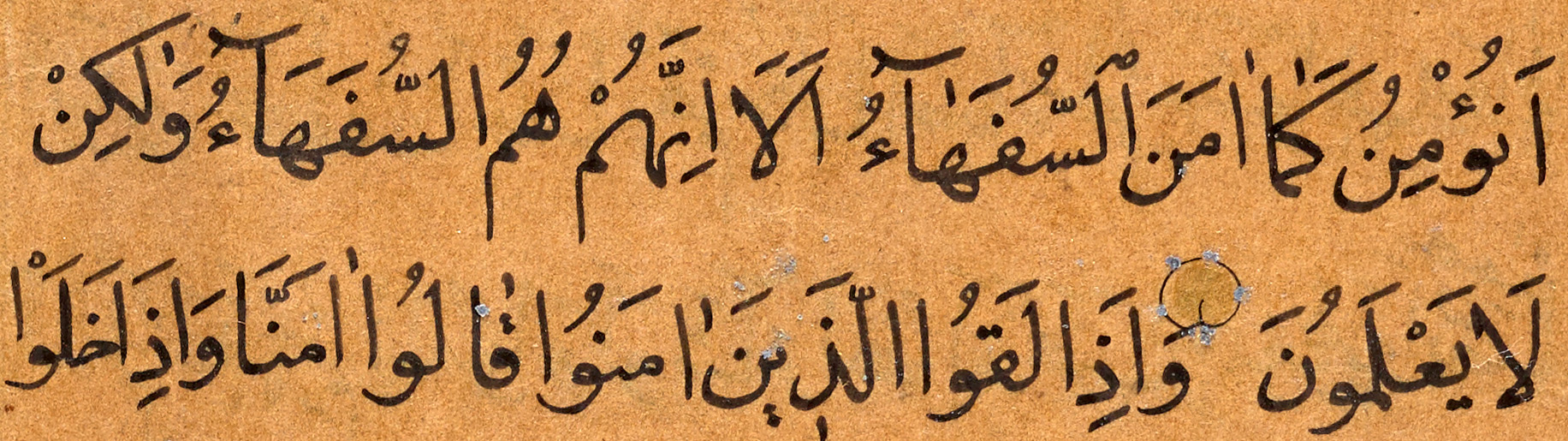

This sixteenth-century Quran manuscript features extensive diacritics, including zer, zabar, pesh, tashdīd, and sukūn (in the form of a circle):

Image credit: Free Library of Philadelphia (Lewis O 3).

Review

In this chapter, we introduced these letters and diacritics:

|

Letter or diacritic |

Name |

Sound |

|

ت |

te ते |

t त |

|

م |

mīm मीम |

m म |

|

ج |

jīm जीम |

j ज |

|

چ |

che चे |

ch च |

|

ّ |

tashdīd तश्दीद |

double consonant |

|

ْ |

sukūn सुकून |

no vowel |

Exercises

Pronounced with the tongue against the back of the teeth, as in thālī.

The distinctive top portion of a letter.

The rounded bottom part of a letter, extending below the baseline. Bowls appear in the independent and final forms of letters including lām, nūn, and sīn.